Listen Up: The Legend of Ronnie Lane

Raise a pint to a musician whose record sales never approached the size of his footloose spirit. Ronnie Lane was quite a person.

I’ve always been a fan of ramshackle rock & roll. Some bands just sound better when they’re sloppy. It just seems more fitting for them.

For instance, the Stones’ crowning achievement, Exile on Main Street, earns major bonus points in my book for being something of an aural bender full of missed notes, shifting rhythms, poor microphone placement, and stoned caterwauling.

My inclination toward this kind of thing is why I’ve always considered the Faces (they were actually called “Faces,” but nobody ever says it that way) to be the single most underrated rock band of all time, bar none.

The Stones, outside of Keith and the damage done, usually pulled their shit together enough to make a professional job of it in the studio. Exile is a battered outlier in their catalog. But the Faces were Guinness-besotted party boys from day one who forever seemed like they were about to collapse on top of each other in a heap.

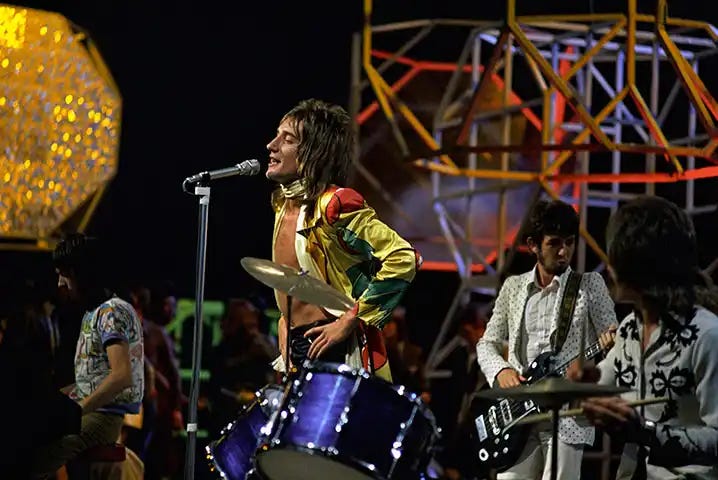

Actually, they did collapse on top of each other in heaps, quite often while laughing hysterically, onstage and in front of paying audiences. One might consider this combustible revelry to be a mere piece of schtick if it weren’t for the fact that they also did it in recording studios, record company offices, pubs, and on the sidewalks of major cities the world over.

These guys had to have spent as much time peeing as they did playing their instruments.

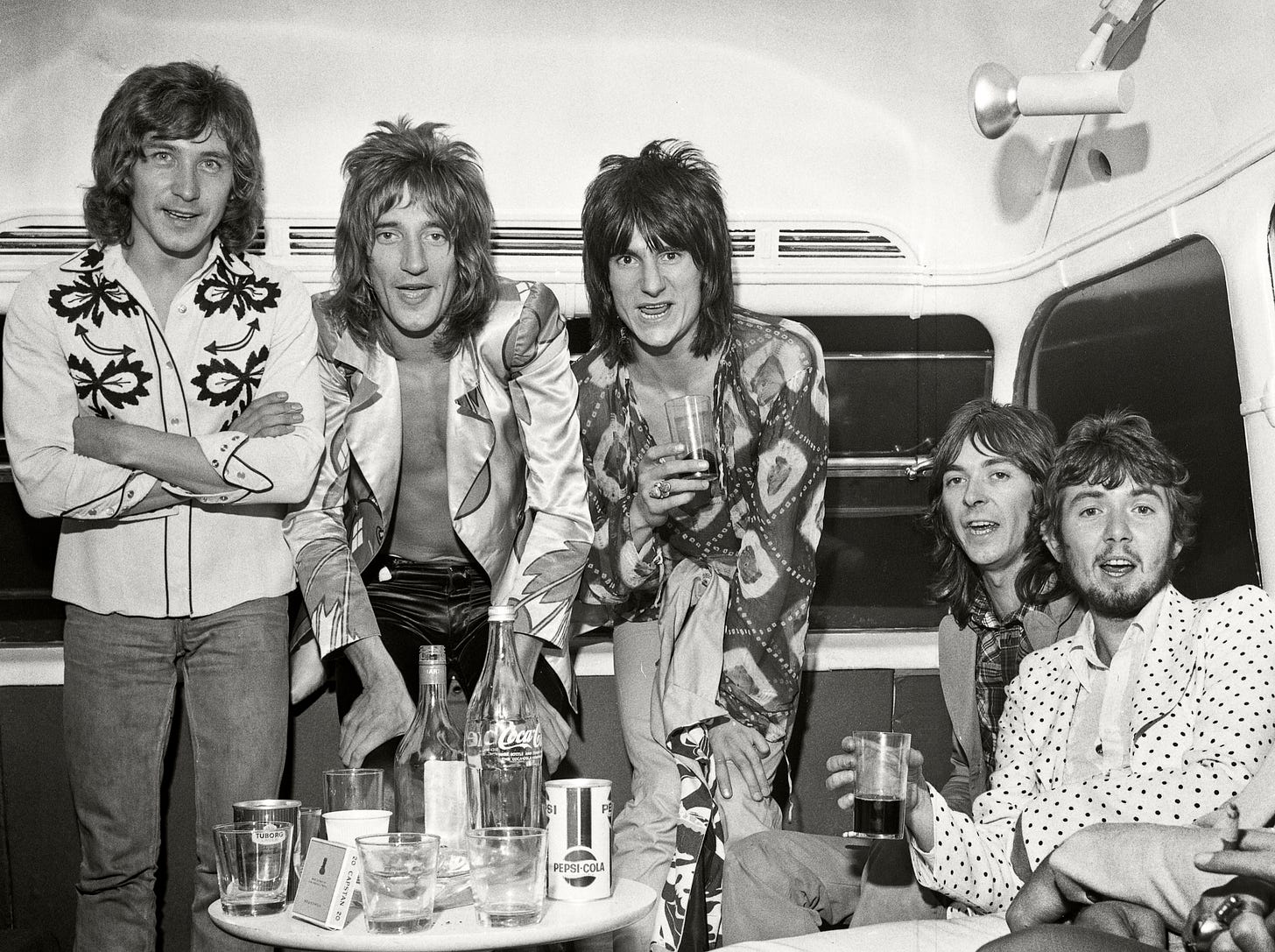

Three of the Faces, Ronnie Lane (bass and songwriting), Kenny Jones (drums), and Ian McLagan (keyboards) began their careers with the Small Faces—they were all short—until lead singer Steve Marriott became a self-satisfied asshole, at which point they booted Marriott, then recruited guitarist Ronnie Wood and vocalist Rod Stewart, who were fleeing the Jeff Beck Group after Beck started suffering from the exact same affliction as Marriott.

For a while, it worked like a charm. The Faces pitched in together and became one of the more popular bands in the world, with all the usual 70s rock star trappings— limos, booze, groupies, private jets, pointlessly smashed hotel rooms, etc. They were having a very good time, and you could hear their boozy joyousness all over their albums.

Here’s a roaring example called “Too Bad,” and, in both its raggedness and “Aren’t we a mess?” lyrical content, it could serve as the group’s thesis statement.

That stands with any Stones rocker from the period, and there’s plenty more than that on the Faces’ four studio albums. But it all fell apart after a while. Just like it always does.

What happened was, lead singer Stewart became way more popular and famous than his rowdy bandmates via a string of classic solo albums that often featured various combinations of the other Faces jamming behind him, albeit uncredited or credited in very small print. Wood and McLagan play on “Maggie May,” for instance, but nobody ever mentions it.

Not surprisingly, Rod the Mod eventually made the magical transition to self-important assholery, just like Marriott and Beck before him.

He became a butt-shaking prima donna, showing up late for gigs and criticizing the other Faces’ playing and songwriting, and he took to camping it up around the stage in silk jackets with no shirt, sparkling gold skintight pants, and flowing feather boas. Granted, he had already been doing that to some degree—The Faces all loved their clothes—but a very strong whiff of “Look at us! We’re Rod Stewart and the Faces!” had developed, and Ronnie Lane, in particular, was none too pleased about it.

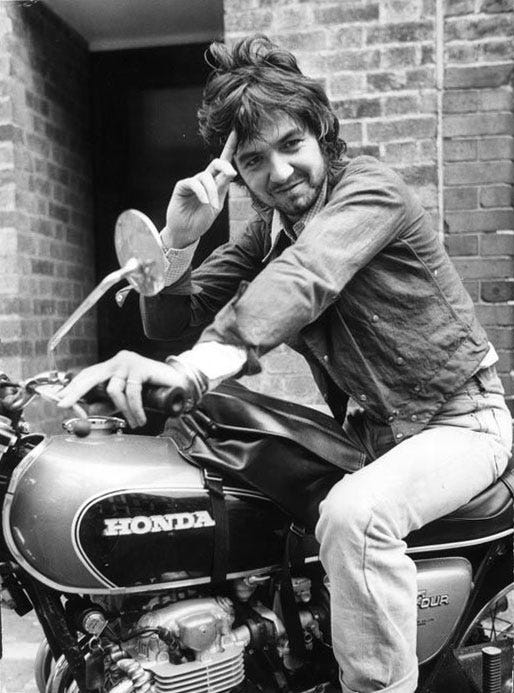

First, Ronnie took to wearing beaten tweed jackets, brown driving caps, and gum-sole work boots, looking for all the world like a gentleman farmer who was badly down on his luck. Or, if you will, he looked like the anti-Rod Stewart.

Then he quit the band.

Lane, you see, was the gentle soul of the Faces. His temper may have flared on occasion, and he whooped it up and repeatedly tumbled down the stairs with everybody else. He was certainly not averse to getting stinking drunk, but he never felt comfortable with the Major Rock Star scene. There was something very humane and emotionally grounded about him.

For proof, look no further than my favorite Faces tune, “Debris,” which Lane wrote and sang about his father, Stanley.

When he was growing up in London’s East End, Lane’s mother developed muscular dystrophy and lost the ability to take care of her children. That left the job to Stanley, who worked as a bus driver and struggled mightily to make ends meet while maintaining a sunny, can-do disposition that had a great impact on young Ronnie.

No matter how hard his day had been on the road and down at the depot, Stanley would come home looking for his two sons, eager to hear about their day. They waited for him to get there. On weekends, Stanley took Ronnie to swap meets that were set up around the East End’s bombed-out ruins—the “debris” of the song’s title—to look for treasures among the junk that other poverty-stricken, post-war British families were trying to unload for a few extra pennies.

Listen to this.

Isn’t that something? Springsteen gets a lot of mileage out of writing about his relationship with his father, and he’s often done it quite powerfully. But I don’t think he’s ever delivered anything as fine as Lane’s work here.

“And I wonder what you would have done without me hanging around.” The empathy of that, to recognize your father as someone who had to set his hopes and dreams aside to raise his kids in a difficult situation.

What a breathtaking piece of music. It’s not especially “rock & roll,” that’s for sure. Rod Stewart is not likely to do a preening rooster walk to it.

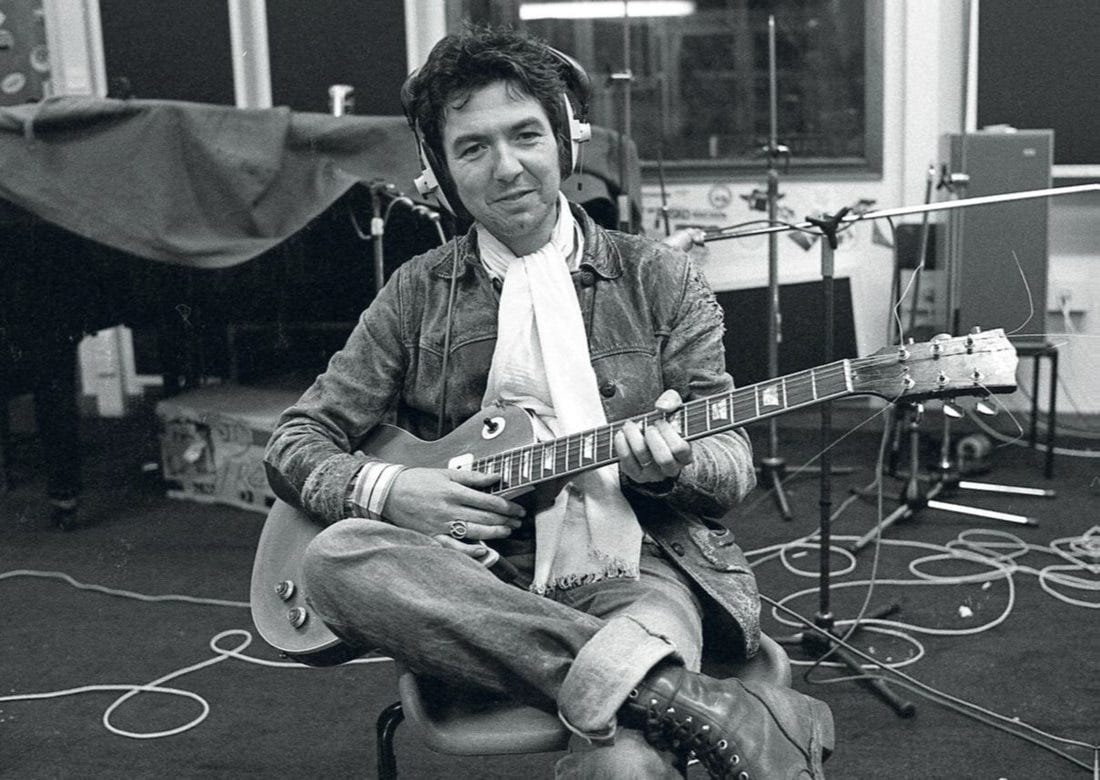

That’s the kind of guy Lane really was. When he left the Faces, he went back to his roots and abandoned all forms of moneyed artifice.

He and his then-wife, Kate, who was a hardcore hippie, bought a crumbling stone farmhouse and a small farm that they had no clue how to run and parked a trailer containing Ronnie’s mobile recording studio, which eventually became his sole form of consistent income when he rented it out to other bands, in the barn.

Then he gathered a bunch of thoroughly charmed, often exasperated musicians in that barn, hung a huge pot of soup over a fire for a few weeks, and recorded a little-known DIY masterpiece full of warmth and acceptance and belief in the better spirits of everyday working people.

People like Ronnie Lane’s dad.

It’s hard for me to focus on just a couple songs from 1974’s Anymore for Anymore. When I tell you there’s not a dud track on it, I’m telling you the truth. It’s something of a British counterpart to the Band’s self-titled roots classic, all muffled thud and thump and swing.

There’s not a guitar solo to be found on Anymore for Anymore. The “sing along now” songs bounce about on accordion, fiddle, clarinet, and barrelhouse piano, and Lane’s battered vocals on the ballads are often enough to break your heart.

The record is filled with compassion and palpable awe at the simple joys of life. Lane’s friends always said he had a philosophical bent about him, and you can certainly hear it in these tunes.

Here’s one of my favorite tracks on the record, “Roll on Babe.”

There’s a casual George Harrison vibe about that— think “Old Brown Shoe.” You sense that the guys playing it get along with each other; the easy, swinging groove feels totally natural. That endlessly sawing fiddle in the left channel is quite lovely.

All of the songs on Anymore for Anymore have similar arrangements to “Roll on Babe.” You can sense the fingers plucking strings and the wood of the piano creaking. The sole exception is a remarkable track called “The Poacher,” in which the sudden, rather shocking appearance of a string quartet turns Lane’s story of a fisherman’s joy in the task at hand into an eloquent, vaguely surreal celebration of hope and promise.

It's fresh and bright and early

I went to watch the river

But nothing still has altered, just the seasons ring a change

There stood this old timer

For all the world's first poacher

His mind upon his tackle and these words upon his mind

Bring me fish with eyes of jewels

And mirrors on their bodies

Bring them strong and bring them bigger than a newborn child

Well, I've no use for riches

And I've no use for power

And I've no use for a broken heart, I'll let this world go by

There stood this old timer

For all the world's first poacher

His mind upon his tackle and these words upon his mind

Bring me fish with eyes of jewels

And mirrors on their bodies

Bring them strong and bring them bigger than a newborn child

My God. That’s some gorgeous writing for a supposed drunken second-stringer to Rod Stewart. In my mind, this is a statement of purpose from Ronnie Lane, the counterpoint to the Faces’ “Too Bad.”

Lane didn’t need the Faces and their excesses. He was pursuing a simpler dream. And that simple dream, coupled with ingratiating naivete and boundless, almost comically unwarranted optimism, turned out to be his real financial undoing.

To promote Anymore for Anymore—and to keep himself moving, because he didn’t like staying put for very long—Lane cooked up the concept of the “Passing Show,” a modified gypsy caravan full of band members, wives, kids, instruments, can-can dancers, fire eaters, unfunny clowns, and a very bad comedian. The Passing Show would appear in towns across the British countryside with virtually no warning, set up a raggedy tent, and perform for whoever showed up and paid a minimal price for a ticket.

As you can imagine, this was not a moneymaking endeavor, and there were evenings when no more than fifteen or so people were in the audience. Lane was no businessman. His entire game plan was to find a bunch of used vans and extremely old buses, throw everything and everyone into them, and head out on the road. Booze, of course, was aplenty.

This was not Dylan’s Columbia Records-financed “Rolling Thunder Review,” although, given that Lane did it first, Dylan may well have lifted the idea whole cloth from Lane. You know, in one of his less visionary moments. (One could argue the Stones did it first with The Rock and Roll Circus, but that was a one-off affair. Nobody was dragging it down the street).

The buses broke down repeatedly, and one night the well-lubricated ringmaster took a dump in a closet. Ronnie didn’t bother to purchase a generator. He and the band would string some extension cords and literally steal electricity from whatever town they stopped in. They were regularly raided by local fire departments.

The whole thing was wildly romantic but nuts. The few people who attended before it all came crashing down remember an evening of great good cheer, touching balladry, and raucous jamming. I imagine it was a blast.

Keyboard player Billy Livsey later said of Ronnie, “Never known a performer like him. He would go onstage absolutely tanked on barley wine, and he’d stare into the crowd with a smile on his face, and the gig would become an instant party.”

But just a few weeks into the sojourn, unpaid band members started bailing. The mess of it was best summed up by a note saxophonist Jimmy Jewell pinned to the caravan the morning he and his family took flight. It read, “Goodbye, cruel circus, I’m off to join the world.”

Lane lost every penny he earned with the Faces courtesy of the Passing Show. He never recovered from it, either, not that he tried very hard. He mostly laughed ruefully about the self-generated fiasco.

He just wanted to play music with his friends. He’d release occasional albums, but, from the money end of things, they were close to an afterthought.

Rather surprisingly, Lane, like the Who’s Pete Townshend, was a devotee of the Indian spiritualist Meher Baba, although Ronnie took Baba’s suggestion to detach from material possessions a lot more seriously than Townshend ever did. Lane became friends with Townshend via their shared love of drinking and Meher Baba, probably in that order.

Lane continued to ably record and tour with a band self-mockingly called Ronnie Lane’s Slim Chance, but arguably his best work after Anymore for Anymore is a 1977 album he recorded with Townshend called Rough Mix. Note that I don’t call it a “duet album.” Lane never really understood it, but Townshend refused to write songs with him! They appear on each other’s songs on the record, but you get one from Pete, then one from Ronnie, then one from Pete, etc.

They got on each other’s nerves. According to Townshend, punches were sometimes thrown in the studio. The album’s sleeve notes actually read, “Ron and Pete play various acoustic and electric guitars, mandolins and bass guitars, banjos, ukuleles, and very involved mind games.”

I guess the friction helped. Rough Mix contains the best solo work of Townshend’s career, a handful of delightfully laid-back folk rockers. The highlight for me, though, is an emotional ode to yet another working-class hero, Lane’s wistful ballad, “Annie.”

Co-written with his wife, Kate, and his buddy, Eric Clapton, but with Lane guiding the lyrics, “Annie” is a tribute to the essence of an old woman who took care of Ronnie and Kate’s children on the farm when they were busy with other things. Ronnie was moved by what a caring and kind-hearted person Annie was while having absolutely nothing to her name. Surely, he saw a lot of himself in her.

Once again, that’s gorgeous. A beautiful little song. For somebody that most rock fans have rarely paid attention to, Ronnie Lane knew what he was doing. He was a gifted writer with a flair for fragile sentiment.

Ronnie had a lot of heart, but he forever seemed to be hanging from a thread. There was always another problem just around the corner for him.

During the sessions for Rough Mix, he started having trouble with his right hand; he was finding it difficult to strum chords. And he was stumbling around a lot, almost falling down while he recorded vocals.

He’d tell everyone he was just tipsy again, but he secretly knew better— he was in the early stages of the multiple sclerosis that was still devastating his mother. He had no delusions about what he was in for, either.

The latter part of Lane’s life consisted of a mighty struggle to find money to live on, an affordable place to live (Austin, TX, for a while), and something to relieve the torment of MS. It wasn’t fun. He would sometimes fall into dark moods and grow frustrated with his plight, as anyone would. But he was beloved by his friends, who would usually marvel at the presence of the laughing, sarcastic Ronnie they always knew. Incredibly, he continued to perform during this period, appearing in bars and small clubs in varying degrees of incapacitation.

In 1983, such illustrious musicians as Jimmy Page, Steve Winwood, Jeff Beck, Eric Clapton, Joe Cocker, Bill Wyman, and Charlie Watts participated in a tour to raise money for both Ronnie and multiple sclerosis research. Lane would often join them onstage in a wheelchair to sing a few tunes at the end of the show.

Ronnie Lane died on June 4, 1997, at the age of 51. A street named after him, cleverly called “Ronnie Lane,” opened in Manor Park, Newham in 2001. He would have gotten a good laugh out of that.

Thank you. I have been lamenting the loss of the rock and roll flute for years without even realizing I'd also been missing the squeeze box. I suppose we have Mr Moog to thank for all that.

I’ve loved Faces and Ronnie Lane for so long, but again, you’ve told the true story behind the impression and enhanced my understanding and experience exponentially. Love you for it.

☮️❤️ and Rhythm🎵and Booze 🥃