Not to read too much into it, but it could be that Count Basie isn’t turning around to look at that guy behind him because he can’t stand the little bastard.

That’s Pee Wee Marquette, who was the doorman and emcee at Birdland, a 1950s jazz club that was named in honor of Charlie Parker, although Bird was eventually barred from appearing on its stage due to his drug-hazed shenanigans. During the day, Pee Wee also labored at a tacky joint on Broadway by the Winter Garden Theater called the Hawaii Kai, which was billed as “the world’s greatest Polynesian restaurant.”

It was not.

The Hawaii Kai—the Bamboo Lounge scenes in “Goodfellas” were shot there—was the kind of place where you passed a waterfall and a cage full of capuchin monkeys on the way in, at which point a lei was ceremoniously draped around your neck. Then you were shown to your table, and you started your meal with a froufrou cocktail that had a little umbrella stuck in it.

Classy.

When the sun went down, Pee Wee worked Birdland, where he’d check i.d.’s and take money at the door, then climb onstage to make introductions before the shows and between sets.

Here’s a sample of his work— it’s the first thing you hear on the classic live album, A Night at Birdland, Vol. 1, by Art Blakey & the Jazz Messengers. The album cooks, by the way. Everybody in this early version of the Messengers could play like crazy, especially Clifford Brown and Horace Silver, who were top-drawer talents.

Pee Wee definitely had a memorably weird stage presence. He could also sing a little bit, and he got to hang out with some of the greatest musical performers of the 20th century. Good for him. But he was a mean, perpetually hustling prick, if stories about him are to be believed. And stories about Pee Wee abound.

The thing Birdland musicians remembered most about Pee Wee, aside from his being a thoroughly dislikable person, was his intentionally botching their names if they didn’t slip him a few bucks before he approached the microphone to introduce them. It didn’t matter how famous they were, either. If you didn’t grease Pee Wee’s palm in advance, he somehow couldn’t remember your name.

Paul Desmond, the Dave Brubeck Quartet’s smoothly brilliant alto man, was one of the wittiest, most erudite of all big-time jazz musicians; the self-penned liner notes from his solo albums read damn near like James Thurber holding a martini.

Desmond was such an operator he dated a string of elegant fashion models, about whom he once said, “Sometimes they go around with guys who are scuffling for a while. But usually they end up marrying some cat with a factory. This is the way the world ends, not with a whim but a banker.”

How many people at your job talk like that?

Anyway, little escaped Desmond’s attention, and he always enjoyed a wry laugh. In his book, Take Five: the Public and Private Lives of Paul Desmond, Brubeck’s manager, Mort Lewis, says that whenever the quartet was booked at Birdland, Desmond would be sure to withhold money from Pee Wee just to hear what he would call him during the introduction.

Here, according to Lewis, is how it usually went:

“Now the world-famous Dave Brubeck Quartet, featuring Joe Dodge on drums and Norman Bates on bass,' and then he’d put his hand over the microphone and turn back to Joe or Norman and say, ‘What’s that cat’s name?’ referring to Paul. Then he would take his hand off the microphone and say, ‘On alto sax, Bud Esmond.' Paul loved that.’”

This, by the way, was the mid-1950s, so it was not yet amusing that Brubeck’s bass player was named Norman Bates. I imagine Desmond made sure everybody knew it was after “Psycho” came out, though.

Pee Wee was also known for leaving the microphone stand down at what would be pretty much any other adult’s waist level when he exited the stage, even though musicians constantly asked him to stop doing it. He would just leave it at a suitable height for him, and the performer had to pull it up himself. Again, Pee Wee wasn’t forgetful. He just did it because he liked being a jerk.

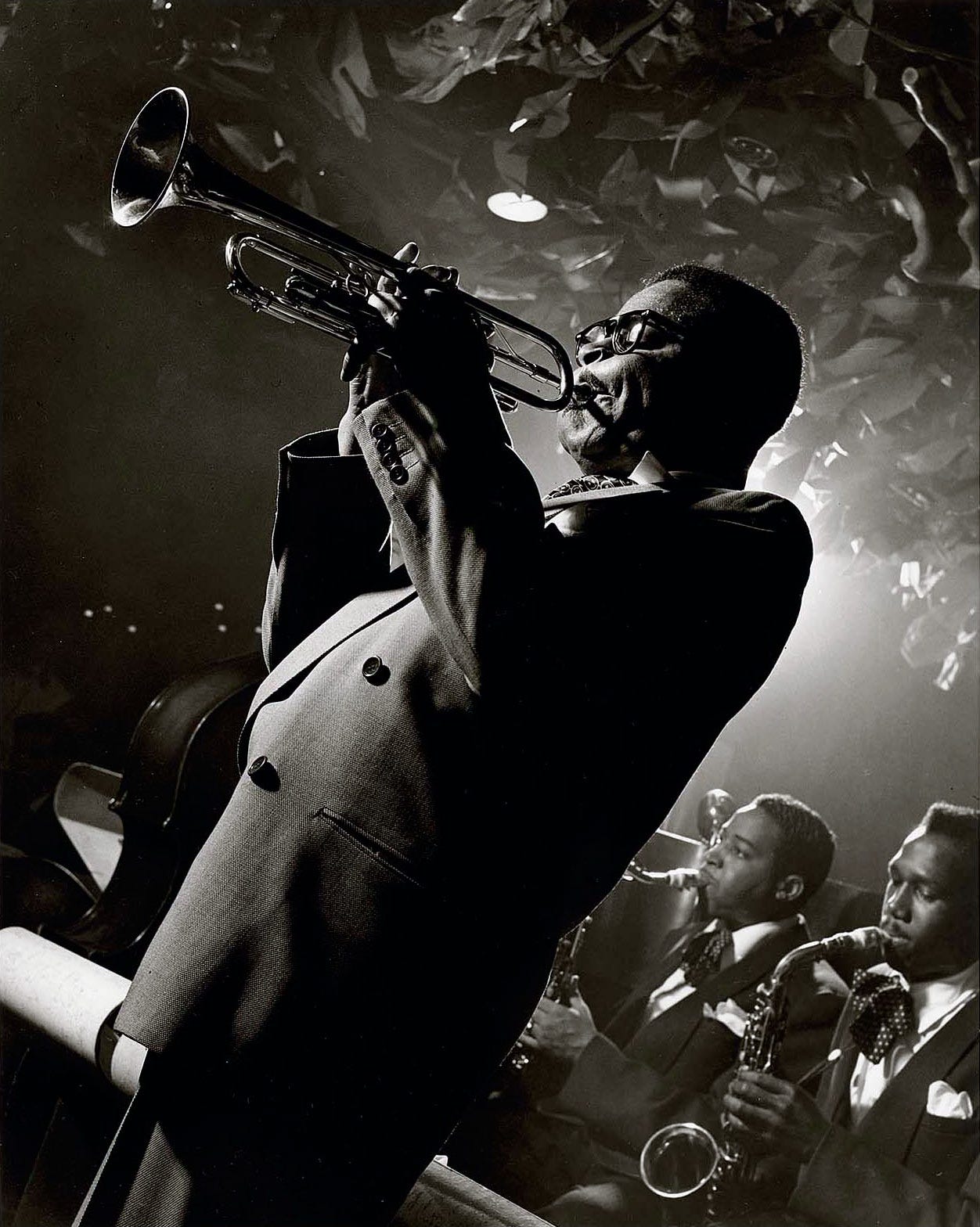

One evening after Pee Wee’s introduction, Dizzy Gillespie walked to the microphone on his knees, counted off the opening tune, and started playing.

You gotta love Diz.

My all-time favorite Pee Wee Marquette story, though, has to be one involving Lester "Prez" Young, who, if you don’t keep up with this sort of thing, was a giant of the tenor saxophone and a genuine character who spoke in a mostly self-invented hipster slang that often had to be interpreted on-the-spot by the listener.

Young, as a matter of fact, has been credited with originating the use of the word “cool” as a signifier of excellence, as in “The Cool Stuff” with Paul Tatara. He may also have been the first person to call money '“bread,” refer to a home as a “crib,” and use “dig” as a way to convey a positive impression. And no one ever said “homeboy” until Young started referring to his then-bandleader Count Basie that way.

So he had a way with words.

Although Young was normally a very sweet, gentle guy, like everybody else, he had his problems with Pee Wee.

Once, after getting his fill of whatever Pee Wee was bitching about that particular evening, Prez summed up the situation quite succinctly when he said, “Get out of my face, you half-a-motherfucker.”

That may well be the greatest putdown I’ve ever heard! You know you’re disliked when people won’t even credit you with being a full motherfucker!

Just reread Oliver Twist. Fagin, Bill Sikes, refer to their hideouts as cribs.

Thank You Thank You Thank You.