I know what you’re thinking— “Oh, Jesus. This nerd can’t be writing about W.C. Fields.”

By now, a full eighty-six years after he died, most people have no real opinion of Fields, if they know anything about him at all outside of his easily impersonated side-mouthed drawl and a few endlessly recycled images of a top hat, a grimace, and a gin-blossomed nose. He seems more a trademark than an actual human being, a faded ghost from a comic past that’s now about as funny as a pair of spats.

That is, if you know what spats are.

But I’m here to tell you W.C. Fields was a genius, a slap-happy surrealist who, at his best, operated at a comic level that was several full decades ahead of his time. Luis Buñuel, for all his snide social commentary and art house credibility, had nothing on Fields, except that he was radical enough to seem politically dangerous. Fields just seemed out of his mind.

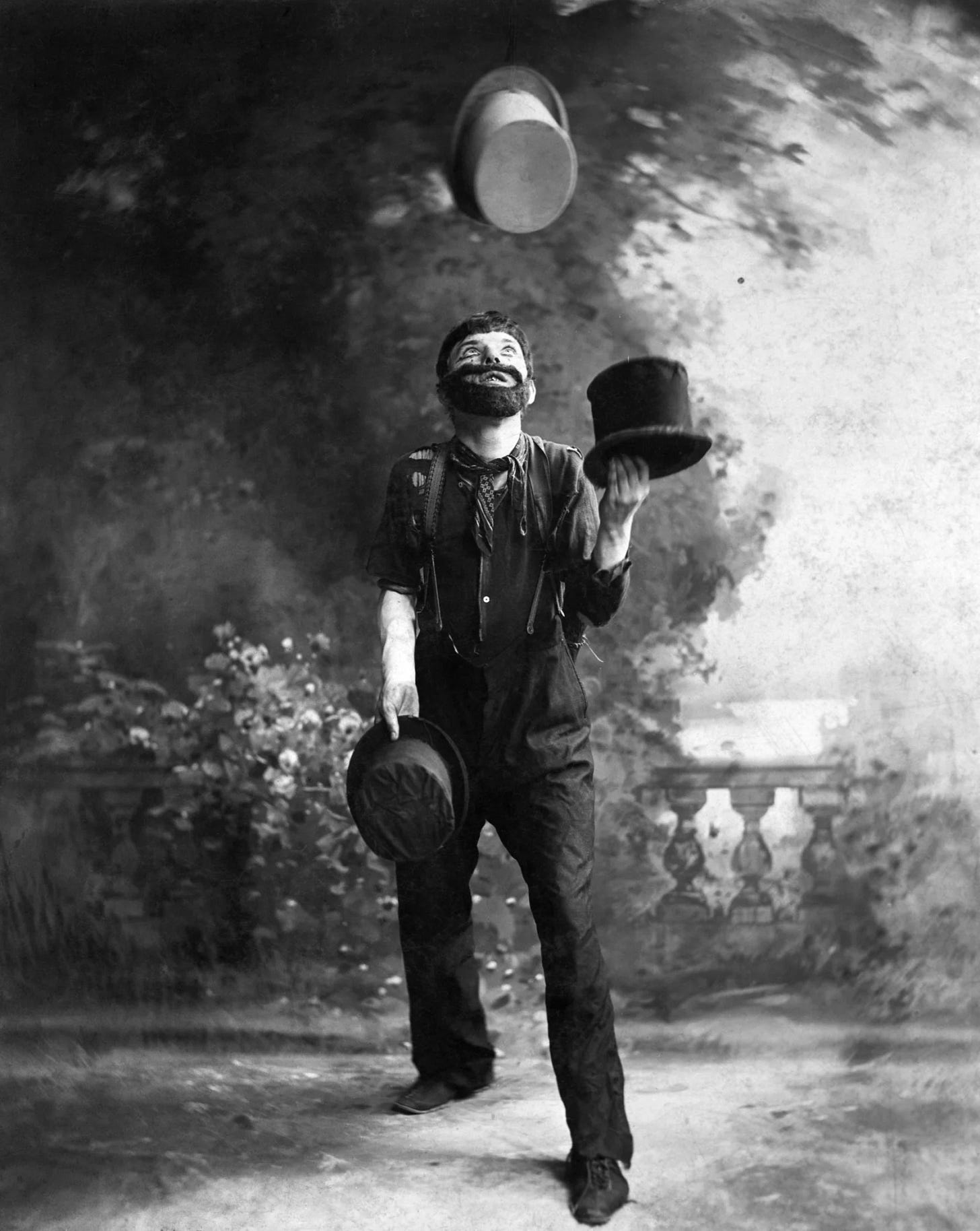

Like his fellow comic royalty, Buster Keaton and Charlie Chaplin, W.C. (William Claude, in case you’ve ever wondered) honed his skills to a gleaming edge onstage years before he ever encountered a movie camera. He was, in fact, a major vaudeville star who was known for his verbal wit, impeccable comic timing, and ridiculously accomplished juggling skills.

The above photo was taken in 1900 when Fields was a mere 20 years old. At this point, he had already been one of the key attractions in the Ziegfeld Follies for over five years, having appeared regularly on Broadway with the Follies as well as when the revue toured overseas. They couldn’t get enough of him at the Moulin Rouge.

In his later motion pictures, Fields would occasionally pull a quick stunt that harkened back to the physical dexterity he displayed during his stage years, then immediately return to his trademark exasperation and misanthropic muttering. But here’s a clip from a 1934 picture called The Old Fashioned Way where he recreates a portion of his vaudeville act.

Honestly— you won’t believe this.

Wow!

The very idea that Fields could be famous for doing something as difficult as that and then proceed to develop an entirely new persona for the movies suggests this guy had a lot more going on in his head than you might initially imagine.

Amazing or not, though, that’s still a pretty traditional circus-style act. The best Fields film moments are wackier than that. They’re wacky in the extreme, coming so far out of left field they’re practically in the stadium parking lot. If you’re not wondering what the hell is going on while you watch him, then he’s not doing his job.

This scene from 1939’s You Can’t Cheat an Honest Man, in which Fields enters into a completely bonkers game of ping pong, is a prime example of what I’m talking about.

“This is getting irksome.”

Fields often showed so much disdain for the bounds of common sense he had to battle the studio to film what he had written. In fact, part of 1941’s Never Give a Sucker an Even Break is framed with Fields, playing himself, pitching the insane story you’re watching to a rightfully flummoxed producer.

Sucker’s narrative, if that’s the proper word for it, opens with Fields falling through the open window of the observation deck on a passenger plane—planes don’t have those—while trying to grab his dropped whiskey flask, only to glide through the air and land next to a beautiful young woman who has never met a man before and lives in a mountaintop retreat with her protective mother, who is named “Mrs. Hemoglobin.”

Then it gets weird. (Fields receives his story credit, by the way, under the pseudonym “Otis Criblecoblis.”)

It’s impossible to say if Fields was soused while imagining this stuff, but he famously drank like a fish. Richard Burton at his self-dramatizing Welshman thirstiest wouldn’t have been able to keep up with him.

Fields’ persistent references to alcohol and being deeply inebriated were not just a comic affectation, like Jack Benny pretending to be a cheapskate or Bob Hope acting like a sniveling coward. Off camera, he poured back bottles of gin and pints of beer with abandon. His doctors told him he’d literally drink himself to death if he didn’t stop, so he chose not to stop, and he died.

He had a razor-sharp mind and was exceptionally well-read, and he finally keeled over from a disease that he somehow managed to choreograph as shtick, to the point that his single most successful work revolved around a virtuous young man falling victim to the evils of drink.

The Fatal Glass of Beer, only 18 minutes long, was officially directed by Clyde Bruckman, but it has Fields’ fingerprints all over it. It may well be the least inventively photographed masterpiece in motion picture history, and its derelict mise-en-scène is thoroughly intentional.

Released in 1933, the picture is a pointedly sarcastic takeoff on turn-of-the-century stage melodramas that were aimed at fresh-off-the-boat immigrants, the kind of people who liked their entertainment blunt and speechy, with a song, a heavy dose of domestic sentimentality, and an overt moral thrown in for good measure (De Niro attends one in The Godfather Part II, if you can remember that scene). Fields also lands a series of sharp blows to the jaw of Depression-era Hollywood cheapies while appearing in the exact thing that he mocks.

Everything about The Fatal Glass of Beer, from its relentlessly uninteresting framing to its poorly connected shots, wooden performances, and stilted dialogue, is faux amateurish and out of synch with viewer expectations. Duck Soup seems like Lawrence of Arabia in comparison. When it was originally released, audiences and critics alike hated it. Fields was accused of being either lazy or jaded or both.

Oh, the Philistines.

The Fatal Glass of Beer actually bears a close resemblance to the disjointed, free-for-all skits that Monty Python launched on an unsuspecting British public in the early 1970s.

Fields, like the Pythons, wasn’t about to waste his time working up coherent segues between his comic musings, and if you weren’t on his wavelength, well, that was your tough luck. And don’t expect him to burst into a winning grin.

Although he doesn’t get around to it in this particular picture, Fields wasn’t above kicking a baby in the ass to make his points...whatever those points might have been. As far as I can tell, the only purpose of The Fatal Glass of Beer, outside of its wack-job deconstructionism, is to flatly illustrate that people are idiots. And who am I to argue with that?

It’s set in “the Yukon” during a crippling “blizzard.” A starving trapper (that would be Fields) and his wife mourn the loss of their son, Chester, who has traveled to the city and hasn’t returned for three long years. Those quotation marks are no accident, since Fields and Bruckman do absolutely nothing to encourage your suspension of disbelief. Throughout The Fatal Glass of Beer, Fields seems bored, if not mortified, to be appearing in his own crummy short.

The moronic characters’ creaky remarks are all the more hilarious because they appear to think their every philosophical utterance is worthy of being carved into marble...a little trick the Coen brothers memorably re-employed fifty years later with Raising Arizona. You get a string of inanities— Fields strumming a dulcimer while wearing a massive pair of woolen mitts, the threatened legal repossession of a Malamute, an innocent country boy winding up in prison because he drank a beer, and a general sense that you’ve suddenly landed on the planet Shitcrazy.

My favorite stretch of the entire loony contraption is a sequence full of wildly mismatched stock footage where Fields takes his sled team, which includes this clearly overtaxed dachshund...

...on a totally pointless search for a lost caribou. Or something.

The first time I stumbled upon The Fatal Glass of Beer on TCM, I was almost crying with laughter. Does it make any sense to say that Fields was utterly precise in his lack of precision? The Fatal Glass of Beer’s guiding principle is to throw it at the wall and see if it sticks, and every inexplicable second of it sticks like glue.

If it hadn’t worked, Fields would be shooting something else in a few weeks anyway. That sense of freedom led to some of the more outlandish gags in movie history and cemented his place in the upper echelon of comedy. How rare that Hollywood would give someone his head, even back in the 1930s, and let him rummage through it unhindered to see what he could find.

I don’t usually include videos in my movie coverage, but you really have to see The Fatal Glass of Beer, in all its awkward majesty, to disbelieve it. So here it is.

You’re welcome. And remember— it ain’t a fit night out for man nor beast.

I really loved this one man! Just shared it on FB.

I'm so happy to see this. Once again, pointing out what deserves to be appreciated. Thank you for your work!