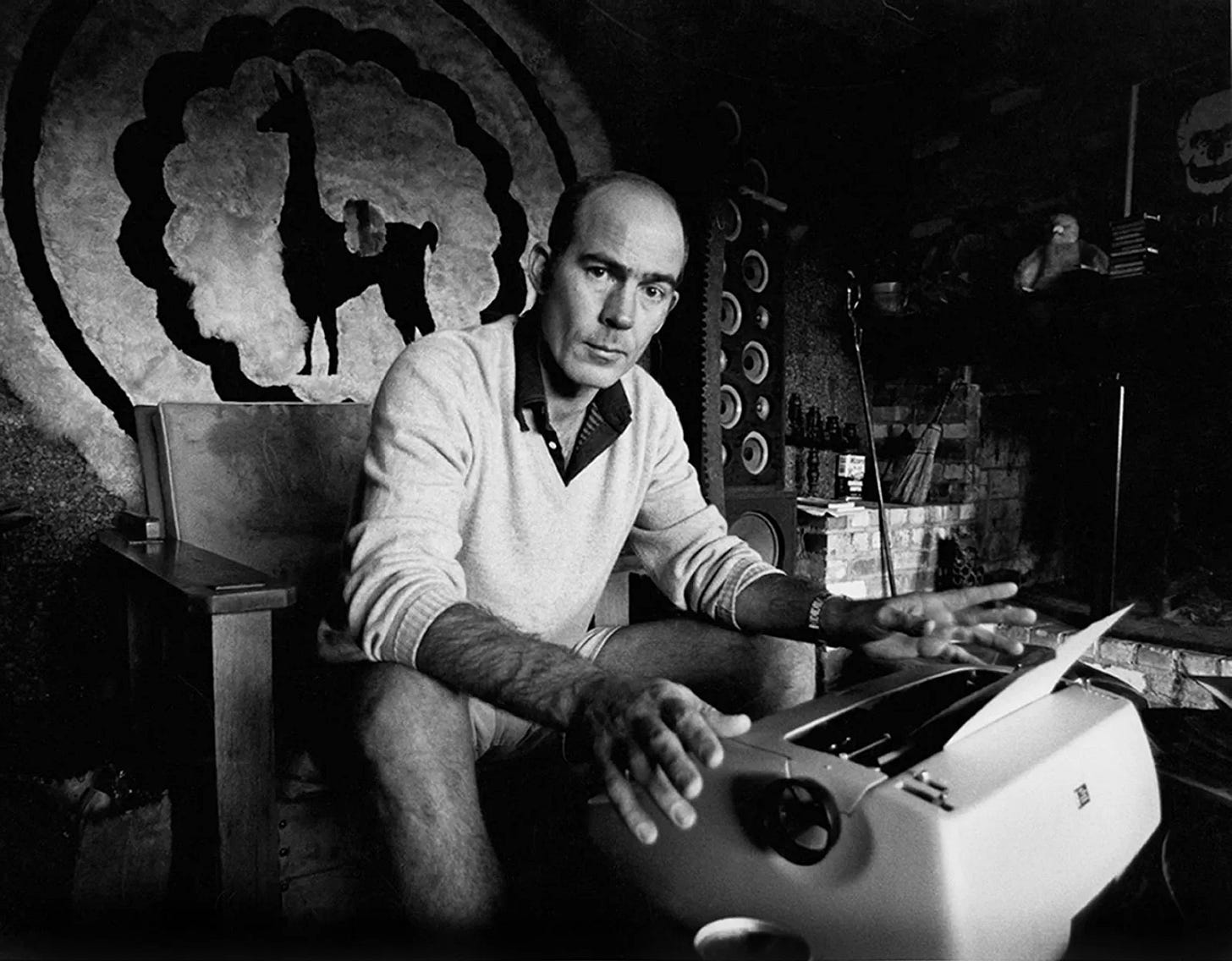

If ever a writer victimized himself by creating an unmaintainable public image, it was Hunter S. Thompson. He’s practically the poster boy for swimming too far from shore.

Thompson should have known better, but he continued drugging, drinking, and freaking out until there was no other option but to pull a Hemingway and stick the barrel of a gun in his mouth. The last time I saw him being interviewed on TV, you could practically smell his synapses burning over the airwaves. The battle against the ol’ fear and loathing finally caught up with him, and it was a depressing thing to see.

But before he fully squeezed the life out of himself, Thompson was a madcap writer with a wild, mocking style that mated Beat-style brooding with hilarious advertisements for an unmoored way of living that works just fine when Rolling Stone is paying the bills but gets to be a bit much when you’re, for instance, holding down a 9 to 5 job and have a boss who expects you to act like a sane human being.

Buffered existence or not (Keith Richards pulled the same trick by being the world’s most coddled junkie), there was more to Thompson than his too-often self-congratulatory insanity.

Although he could be an open-throttle fount of political and social insight—no other journalist, straight or bent, was as proficient at finding the oblique hook in a news story—I’ve always felt the defining element of Thompson’s best work is a palpable humanism that simply refuses to die as he battles The Machinery. His outrage hinged on a rather touching desire for utopian acceptance that was forever being trampled by overseers (elected and sometimes self-appointed), men in suits and uniforms who acted like mere “swine,” “brutes,” and “jackals.”

“Real happiness, in politics,” Thompson once wrote, “is a wide-open hammer shot on some poor bastard who knows he's been trapped but can't flee.”

The underlying sickness of this country, which appears to have finally become its horrific undoing, is that the system isn’t really working for you and me, not most of the time, anyway. Despite the much-ballyhooed promise of the Constitution, the vast majority of us are really just passengers hanging on for dear life while elected officials fuck us over.

Maybe you’ve heard about this.

Thompson could be downright gleeful when the people responsible for this charade got their comeuppance. And even when he knew they would get away with it, and they usually did, he made sure everyone recognized they were little more than two-faced vampires.

He came after them at unique angles, too. Only Thompson would describe Nixon aide Charles Colson’s testicles contracting into his body when he realized the cover was being blown off the Watergate break-in. It isn’t poetry, or even journalism, if you want to get technical about it. But it cuts to what Thompson liked to call “the crux of the matter” in one outrageous image.

Therein lies Thompson’s charm. He was a typewriter-lugging Don Quixote who entered the rumble on coke, speed, and mescaline. His windmill was the corrupt status quo, and he flailed at it with extraordinarily unhinged zeal. For about seven or eight years there, he was one absolutely hellacious writer.

He was Gonzo, and everybody else just had to get out of the way.

Alex Gibney’s Gonzo: The Life and Work of Dr. Hunter S. Thompson is an often ferociously entertaining documentary that doesn’t shy away from the fact that the good doctor was capable of being a giant asshole when he felt like it, and it doesn’t throw up a smokescreen to cover his collapse.

This film is one hell of a “don’t try this at home” story, but much of it, just like Thompson’s writing, is deeply moving and very, very funny.

Gibney has every reason to fly over the top with his visuals, and he often does. He plays around a lot with his graphics, and it can get a tad annoying. But he generally handles the material with commendable restraint. There’s also a great soundtrack by such iconic bell-ringers as Dylan, the Stones, and Creedence Clearwater Revival. Those tunes don’t come cheap, and documentaries seldom make any money. So it seems likely the musicians cut their rates to be involved in a film about someone they respected.

You get talking heads like Jann Wenner, Tom Wolfe, Jimmy Carter, Pat Buchanan, and a bevy of Thompson’s lesser-known friends and relatives, interspersed with amusing TV appearances by Thompson and footage of such earth-shaking events as the ’68 Chicago riots and the fall of the Nixon White House. (Johnny Depp reads passages from Thompson’s writing in voiceover throughout the movie.)

Thompson collapsed into periodic banshee screams while covering many of the key events of the Vietnam era, but he did it while standing up for so-called “freaks” who, at the very least, knew not to follow the manipulative, tight-assed frauds who had been elected as America’s leaders. This worked just fine much of the time but could also lead to situations like his being beaten to a bloody pulp by a battalion of Hell’s Angels.

As Wolfe points out in the movie, in 1965 Thompson was truly “imbedded” with the Angels—he bought a bike and actually rode with them for a year—while researching what would become his first great book, Hell’s Angels: The Strange and Terrible Saga of the Outlaw Motorcycle Gangs (highly recommended). “Imbedding” is an utterly apt description of Thompson’s approach. Throughout his career, he’d bury himself in his subject matter, then report from deep within both the story itself and his own jabbering psyche.

Gibney, by the way, includes Hell’s Angels’ most harrowing passage— Thompson’s description of a horrifying gang rape that he witnessed at an Angels’ “party.” Thompson’s mixture of cold journalistic description and overwhelming moral devastation matches anything Truman Capote cooked up for In Cold Blood. Again, at his best, this guy was magnificent.

But, after making an ill-fated run to become the sheriff of Pitkin County, Colorado (he nearly made it, too, scaring the holy bejeebies out of Aspen-dwellers who still believed in good old-fashioned Law and Order), Thompson would abandon the relatively traditional reportage of Hell’s Angels for a manic, years-long baying-at-the-moon odyssey that carried him through the marble hallways and shady alleyways of the American fiasco.

It all started in Vegas. What happened when Thompson was there did not stay there.

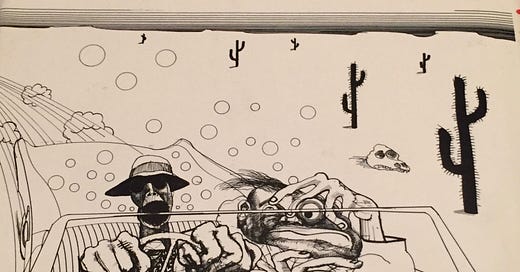

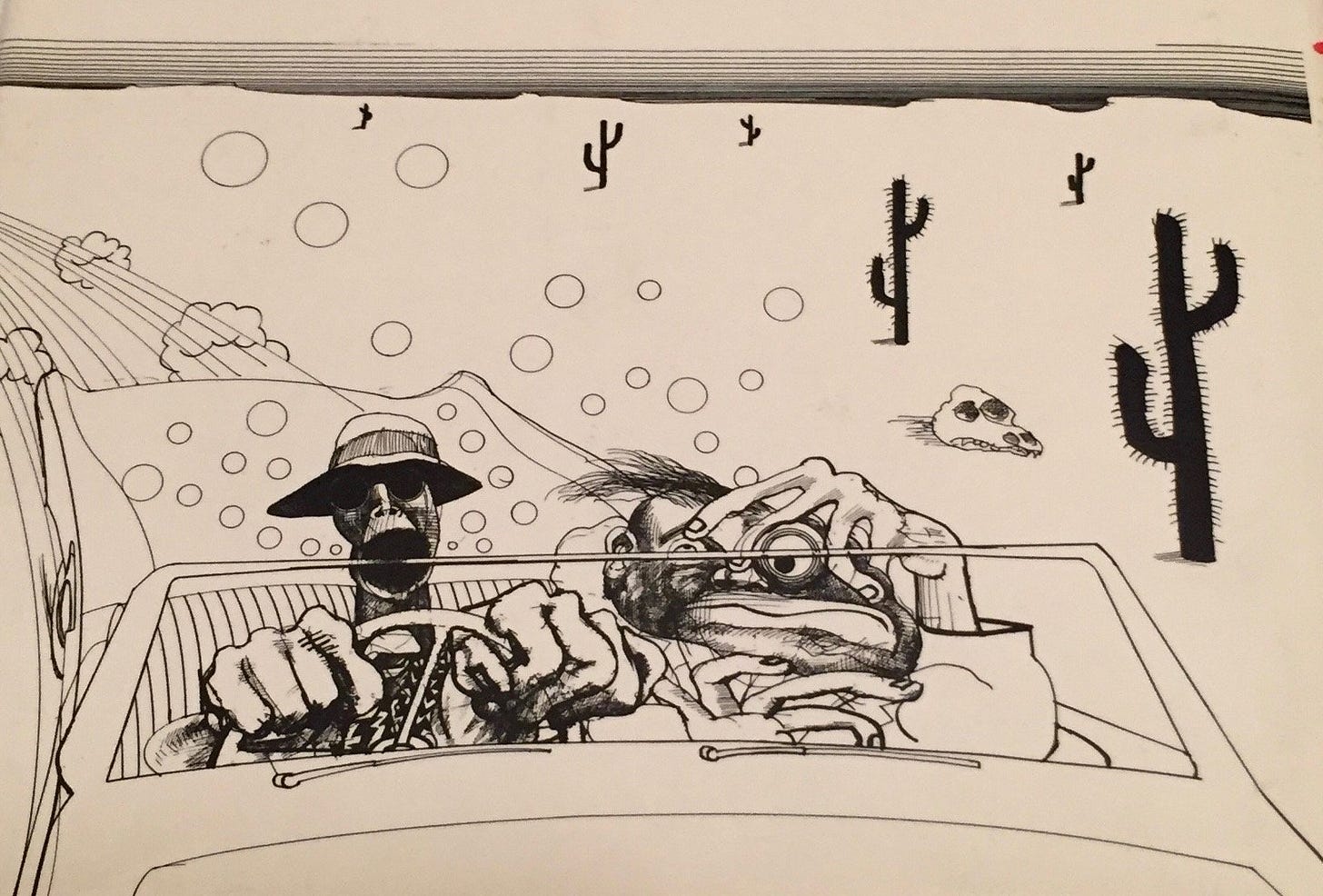

Even casual fans are familiar with the trippy, pitch-black comic novella, Fear and Loathing in Las Vegas. But Gibney makes it clear that there was a lot more going on in Thompson’s work than hallucinated bats swooping down at his swerving convertible.

Fear and Loathing is a fireworks display going off in Thompson’s head. Its depth arises from Roman candles slowly transforming themselves into warning flares. Thompson felt the full weight of the post-Sixties crash not long after the Rolling Stones started crying for shelter, and he surfed the same wave of dread that darkened Altamont. He was just a lot funnier than the Stones were while he surfed it.

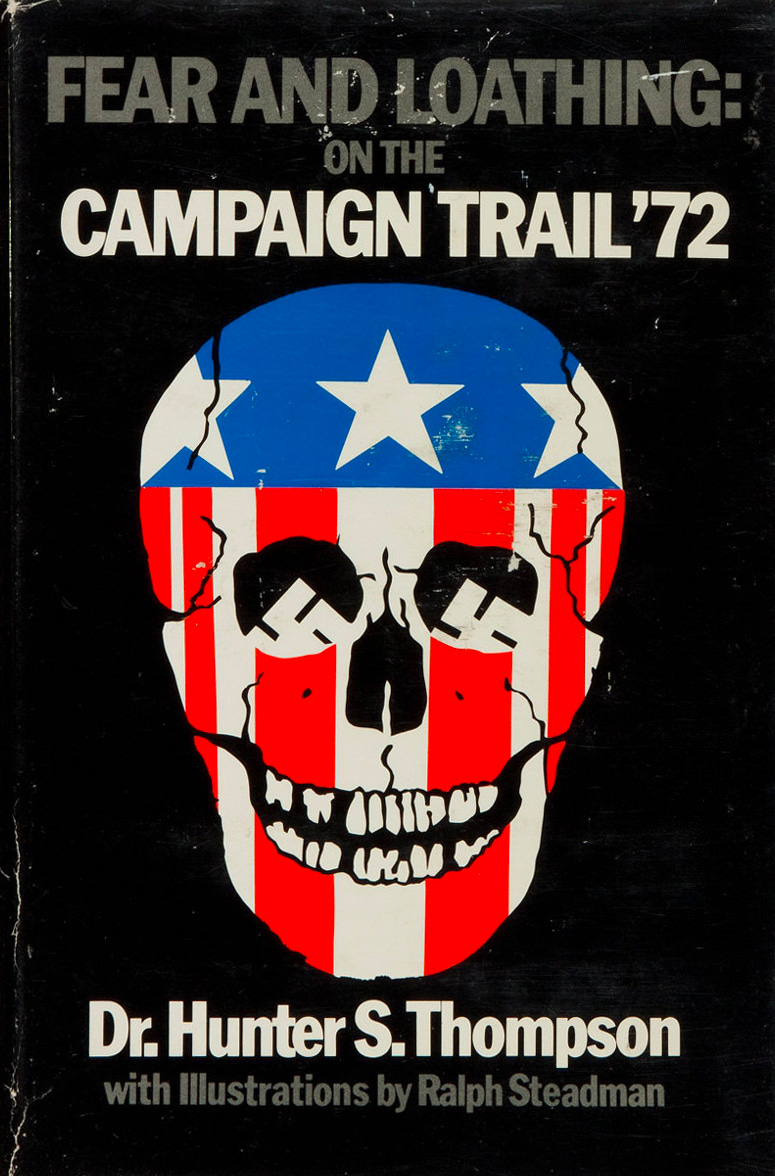

I’ve long felt, though, that Thompson’s crowning achievement is Fear and Loathing on the Campaign Trail, ’72, in which he hops the press bus and follows George McGovern while he attempts to wrest the presidential crown away from one Richard M. Nixon. Rather surprisingly, Gibney spends more time on this stage of Thompson’s life than on any of the others, and the details—including many that are laid out for us by McGovern and his then-campaign manager, Gary Hart—are a blast to hear.

There’s never been a better book written on the American electoral process than Campaign Trail, but you have to stay on your toes while you read it. Even Thompson was surprised that people believed him when he wandered rather fantastically into a theory that Democratic frontrunner Edmund Muskie was addicted to a powerful tribal hallucinogen called Ibogaine!

One of the funnier clips in Gonzo is Thompson nonchalantly explaining on a talk show that he knew for certain this heinous rumor started when Muskie’s campaign hit Miami because he was the one who started it. But don’t let that keep you away from the book. It’s down and dirty stuff, told from the point of view of a political junkie who had already seen too much but couldn’t make himself look away.

Nixon wins, by the way.

The most astonishing thing in Gonzo may well be the opening sequence, in which Thompson dumps the football story he was working on for ESPN.com and writes about the hijacked passenger planes that just took down the World Trade Center. His impressions of exactly where this heinous act would lead us are eerily precise and illustrate just how perceptive he really was, even when he was well past his prime. There’s this:

“The towers are gone now, reduced to bloody rubble, along with all hopes for Peace in Our Time, in the United States or any other country. Make no mistake about it: We are At War now —with somebody—and we will stay At War with that mysterious Enemy for the rest of our lives.”

and this…

“It will be a Religious War, a sort of Christian jihad, fueled by religious hatred and led by merciless fanatics on both sides. It will be guerrilla warfare on a global scale, with no front lines and no identifiable enemy.”

Four years later, Thompson would take himself out of the game for good, but passages like that make you wonder what he could have accomplished if he hadn’t burned himself out on the road to pseudo-freedom.

The sad truth of the matter is that we need Hunter S. Thompson now as much as we ever have. Dear God, do we need him! As he made abundantly clear, through language that virtually crackled on the page, the swine and jackals will forever be circling for fresh carcasses.

They’ll forever be circling for you and me.

Great writing, Paul

Will have to watch “Gonzo.”

I rank “Campaign Trail ‘72” second among the campaign books I’ve read behind Richard Ben Cramer’s “What It Takes,” but they’re different books: Cramer was trying to swallow everything, while Thompson was sending dispatches.

Highly recommend Timothy Crouse’s “The Boys on the Bus” as a companion to “Campaign Trail ‘72.” Crouse was literally Thompson’s ride-along and offers his take on the other correspondents.