R. Crumb and His Race Records

It's complicated.

Every page of Dan Nadel’s new biography of the legendary underground cartoonist Robert Crumb, Crumb: A Cartoonist’s Life, is fascinating. I read tons of biographies, and this one stands with Simon Callow’s drolly opinionated, multi-volume examination of Orson Welles as a personal favorite.

I really enjoyed it, even though I have reservations about Crumb himself. And I’m not the only one.

R. Crumb, in case you don’t know, is a deeply problematic figure. Spurred on by far too many gobbled tabs of acid and lots of other illicit chemicals, Crumb’s iconoclastic work in the 1960s is filled to bursting with surrealistic, troubling depictions of the American Experiment.

Crumb’s childhood home was an enclosed nightmare of physical intimidation, psychological violence, racism, and assorted outré sexual dysfunction, albeit papered over with a smooth veneer of 1950s conformity. He and his equally intelligent, gifted brothers, Charles and Maxon, tried to escape the terror by drawing an endless series of comic books together during their childhood, but only Robert, out of the three, would ever be able to function in normal society. Their sisters, Carol and Sandra, also wrestled demons throughout their adult lives.

Crumb finally built up the nerve to flee the premises in his early 20s, landing a job designing cards for American Greetings in Cleveland. He met a young woman, and they married, even though neither one of them was capable of that kind of commitment. When they became acidheads, they moved straight to Haight-Ashbury, as acidheads were prone to do at the time.

The horrors of his upbringing warped Crumb, and he knew there were other people out there with the same experience, even though they never talked about it. So, egged on by the drugs, he took to illustrating his personal anguish like an obscene Groucho Marx, knowing he’d get heat from people who didn’t recognize he was throwing the curtains back on social brutality in order to confront it, not to celebrate it.

He couldn’t fully explain many of the more distasteful things he drew, but he drew them anyway.

After all, he had insider information.

Much of Crumb’s work is scathing satire and quite brilliant in its presentation. His ever-evolving drawing style, full of lovingly cross-hatched detail, is beyond reproach. But a lot of what he did at the peak of his drugged-up notoriety, and in occasional repellant bursts later on, was (and still is) exceptionally ugly, so ugly, in fact, that I’m choosing not to post an example of it at The Cool Stuff. You can find it somewhere else easily enough.

Blatant misogyny and sexual humiliation abound in these strips, as do racist stereotypes, and they’re often presented via imagery that looks like a perverted take on 1930s magazine ads or product labels. There’s a bouncy goofiness to them as they repel, which makes them even worse, if you ask me.

But here’s the thing— misogyny, violence, and racism are woven into the fabric of this country. We tell ourselves otherwise in our various approaches to maintaining sanity, but that’s a fact; frankly, it’s how we got where we are right now. The rot is now approaching full bloom.

There are a great many Crumb strips that I can’t even look at in good conscience; I couldn’t “enjoy” them in any sense of the word. But I understand what he was getting at.

He rubbed our noses in our convenient delusions.

Like I said, he’s a deeply problematic figure. “The joke’s on you” doesn’t cover it. In Crumb’s work, the joke is on everybody, including Crumb himself. And they can be very nasty jokes indeed.

He knew he was creepy, but he went for it anyway, thus poking at the creep in all of us. Or, at least, making us confront the fact that such creepiness exists in all walks of life.

It was a decidedly weird calling with more than a hint of self-hatred to it.

However...

When he found the love of an equally blunt and outrageous woman (Aline Kominsky-Crumb, who went on to become a groundbreaking feminist comic book artist in her own right and often worked in tandem with Robert; she passed away in 2022), Crumb quit taking drugs, cleared his head, and finally grasped that his work was capable of truly hurting people, even if it served as a personal catharsis. He had many Black and female fans who understood his vibe, but a lot of folks were extremely offended, and you can’t blame them for that.

As I see it, he evolved into an intensely shitty cartoonist version of Randy Newman, minus any degree of Newman’s all-important empathy. His focus on unspeakable topics grew to be less about satire and more about making readers recoil over what he had mockingly written and illustrated.

The ego took over— no one could tell R. Crumb what to do!

So he largely, though not totally, pulled back from that kind of thing. He was still capable of ghastly surrealism, and his very specific sexual obsessions would take on starring roles in many of his stories, to the point that even his biggest fans must have gotten sick to death of dealing with them.

But an unexpected new outlet for his work suddenly appeared, and it was driven by a very real humanism.

Although he once drew an iconic Janis Joplin album cover simply because he was friendly with Joplin, Crumb had no use for modern rock & roll. He even turned down $10,000 when he badly needed it to create the cover of the Rolling Stones’ classic album, Sticky Fingers, because he couldn’t stand the band’s noisiness and “faux authenticity.”

Crumb had long felt that the popular culture of the early 20th century was more honest and real than the corporatized, modern version he was forced to endure in daily life. When he was 15, he even started walking into the “bad” (i.e. “Black”) part of Philadelphia, where he knocked on random doors, seeking out old blues and jazz recordings from the 1920s, 30s, and 40s.

By the mid-60s, Crumb, who even dressed like a traveling salesman from another time, had collected well over one thousand old shellacs and was fully obsessed with their ghostly sounds. Somehow, he felt emotionally connected to them.

What he was doing, of course, was immersing himself in Black culture that had not yet been watered down by white musicians for white audiences, and he’s still doing it today. Crumb’s collection of rare 78s, one of the best in the world, isn’t focused solely on Black artists, but they’re quite obviously its guiding spirits.

You only have to hear a couple of these recordings to understand why Crumb wanted nothing to do with an album where Mick Jagger mugs his way through “You Gotta Move.”

These platters featuring Black performers were called “race records” when they were originally released. No self-respecting white person back in the day would want to be seen purchasing one, let alone listening to it. You have to assume whites avoided them because they’re teeming with a humanity that they didn’t want to admit belonged to dark-skinned people, and the Black vernacular could be shockingly blunt for so-called “polite” society.

It’s all right there on the surface— sex and anger and humor and pain and joy and love and jealousy and violence. And it’s often beautifully written and performed by artists who, consciously or not, were rising above the overbearing bullshit of the white world.

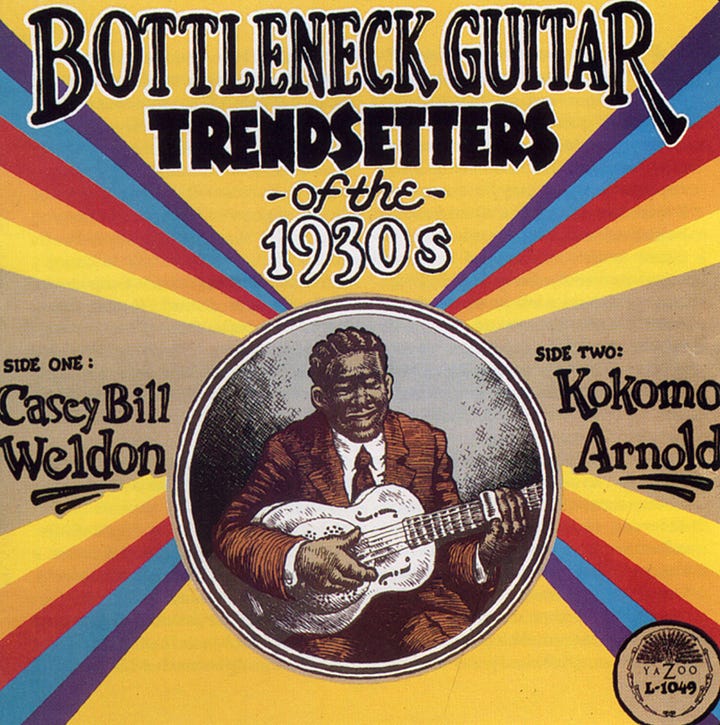

By the 1980s, a great deal of Crumb’s work focused on this music and these now-forgotten musicians. He started drawing early jazz and blues album covers—and supplying many of the recordings found on the compilations—that sometimes utilized the racial tropes of that period’s graphics while imbuing them with a life and energy that put the lie to their outdated concepts.

Crumb pushes things to the edge with a couple of these, but with a vastly different aim than he had before. These are celebrations, characters striding through ancient stereotypes with confidence and swagger. There’s an implied “fuck you” to America’s past here that stands as an embrace of artists who received little recognition, financial or otherwise, when they were still alive.

Some people may not get it, and I accept that. But I really do feel that’s what he’s up to. There’s simply too much warmth on display in his blues and jazz illustrations for it to mean anything else.

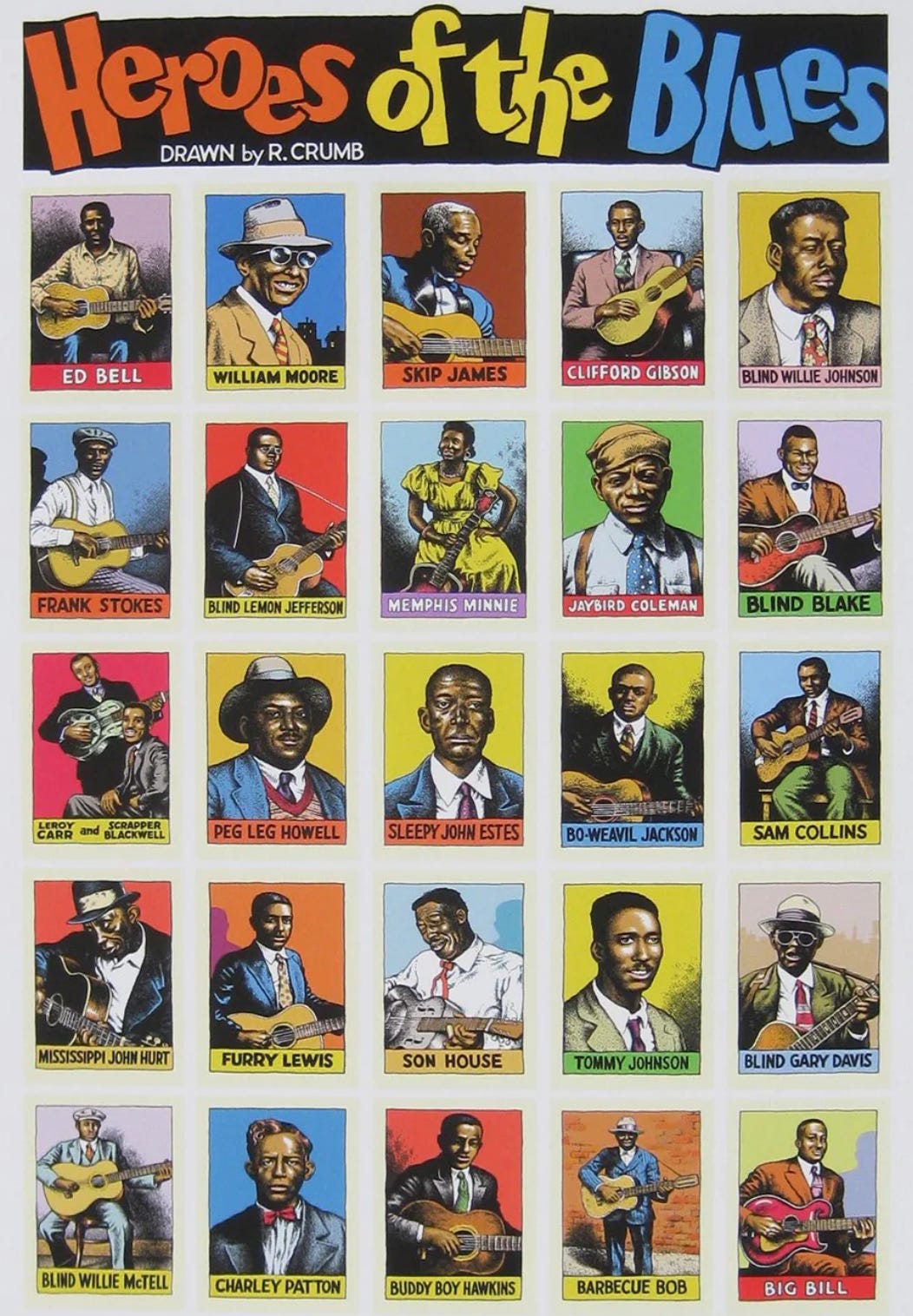

In 1980, Crumb drew and released a series of cards honoring many of his favorite musicians, not all of them famous. There’s a Heroes of the Blues set as well as Early Jazz Greats and Pioneers of Country Music sets, and they’re lovingly rendered little collectables of a bygone era that can still echo in the heart of any music listener who believes in the continuation of our shared spirit.

Aren’t those great? There’s a box of the jazz cards being shipped to me as I write this. I’ll treat myself to the blues set the next time I’m feeling down...which shouldn’t be too long at all, the way things are going.

There’s real dignity in this. It’s not a joke or a perverse commentary on anything. I probably never would have heard of this musician had Crumb not drawn him. That, to me, is a public service.

At long last, let’s hear it for Bo-Weavil Jackson. I hope he knows there’s a skinny white guy up in Harlem (that would be me) who’s saluting him.

I’m a fan of post-WWII blues giants like Muddy Waters, Howlin’ Wolf, Little Walter, and Jimmy Reed, and I’ve searched out a few even older blues players over the past several years, with prime tracks by Blind Willie Johnson and Memphis Minnie being a regular feature of my streaming. But I’ve never pursued this stuff as fully as I have since I read this Crumb biography, and oh my God, have I been missing out on a treasure trove of evocative music!

I haven’t even scratched the surface of what’s available, and I’m thrilled about that. I’ll be getting into these musicians the same way I all but marinated my soul in jazz and roots reggae when I had similar musical revelations in the past.

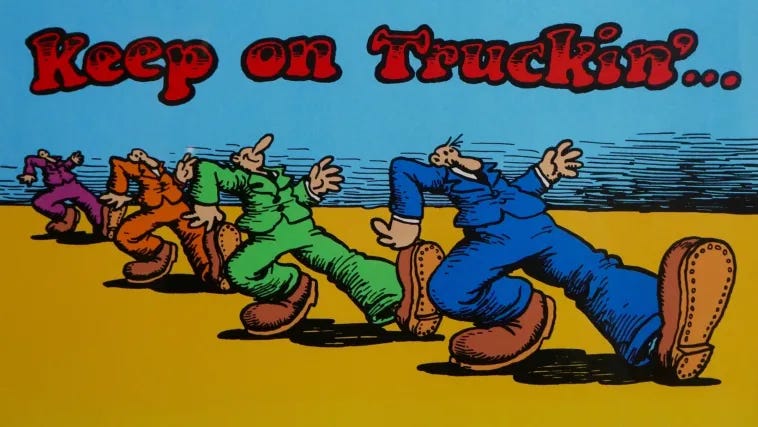

So let’s close this post with some great music that will explain a popular piece of R. Crumb ephemera. You may or may not realize that Crumb is responsible for this image...

Crumb has said that his being convinced to hire a lawyer to sue the scores of people who were using variations of this drawing without his permission in the early 1970s was the only thing that kept him afloat for several years! It generated far more income than he could manage with his comics, random posters, and magazine illustrations.

But what does “Keep on Truckin’” actually mean? Well, here’s Blind Boy Fuller to tell you.

Now you know.

I was planning to play you a track by somebody else right now, but since I’ve been listening to everything I can find by Blind Boy Fuller for the past several days, let’s give him an encore. This one is so great in every conceivable way I almost yelped in front of strangers when I heard it for the first time while riding on the subway.

Dig that vocal and the guitar work! Every song in this collection is tremendous. I can’t recommend it enough.

There are many compilations of old race records and discs devoted to individual performers from the period available for streaming. Try these out as an inroduction: Blind Boy Fuller- Piedmont Blues Stomp, Various- Country Blues: Rough Guide to Unsung Heroes, Bukka White- Parchman Farm, Various- Memphis Blues Singers, Vol. I, and Bo Carter- Banana in Your Fruit Basket.

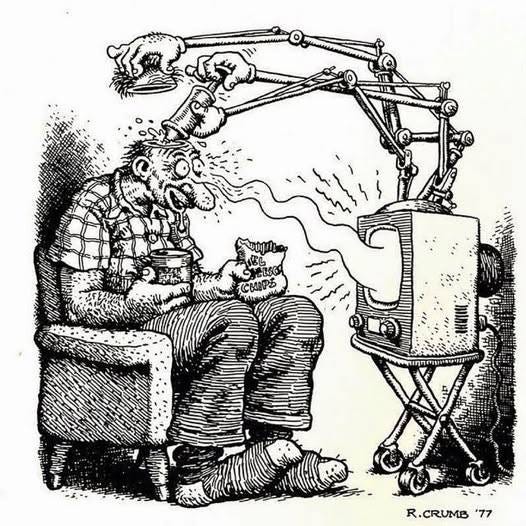

Now look for some others. Enjoy the thrill of discovery, and groove to the mystery of it all. If you ask me, that’s the entire point of life, as opposed to eating, watching, listening to, and buying crap until you’re finally dead.

Surely, you’ve encountered that sort of thing before.

Great piece on Crumb.! I’m almost done with the book. This is excellent supplementary reading.

I’ve many of the early Zaps saved from the 60s, and I used to compare him to Aubrey Beardsley.

Also have his Bible of Filth, which is wild and, well, filthy.

“Crumb” (the book) offers insights and perspective through really nice writing.

Great, intelligent, interesting, multi-layered look at a complex, often unsettling figure: Mr. Crumb.

You open many doors in my brain always Paul. (most are empty closets!)

I'll take a look at the bio on iBooks, read a sample first.

I saw the documentary years ago. Humans have so many ways to be in their own bizarre bubble. An unsettling look into Crumb and family.

Crumb lived in a N. California town called Winters before moving to France.

I lived @12 miles east in Davis, CA.

I'd see him and wife strolling in town occasionally. He also played in a local band "The Cheap Suit Serenaders." Jazz with a roots music underpinning.

I'd see their posters in town announcing shows… I think I saw them at playing at the Davis farmer's market one time.

After he and wife left for France, they rented their Winters home to an acquaintance of mine. I attended a party there one time and was amused to be in the Crumb home.

My mom had many 78s and she introduced me to various jazz and blues artists from the 1940s, 50s… maybe 30's ("albums" comprised of many records in a bound book-like format, each disc in pages of separate sleeve) She was a my music maven.

Thanks for the selection of songs and recommendations of artists. Really good.

That one Blind Boy Fuller - Vol 2 cut had me good.

I'll tell ya, if you didn't know you'd swear it was Dan Hicks… similar voice, Dan loved that style.

Now we know a little more about Dan and his influences.

Maybe a quirky film someday about Dan.

Speaking of quirky and off this topic, Mike Leigh's "Life is Sweet.". One to see.

Thanks again, Paul