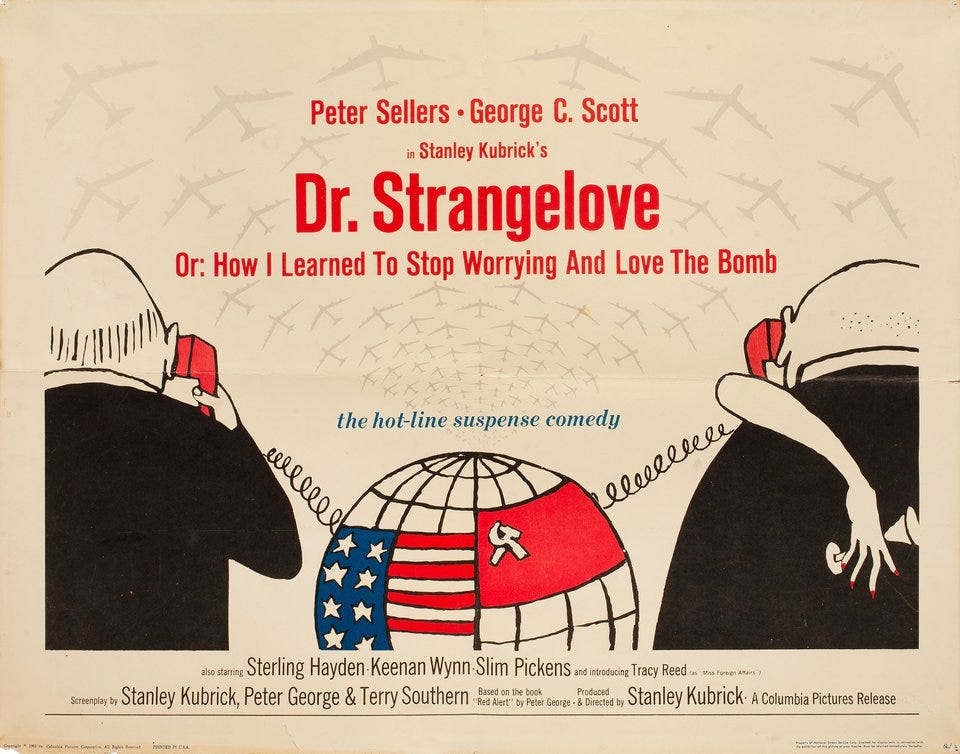

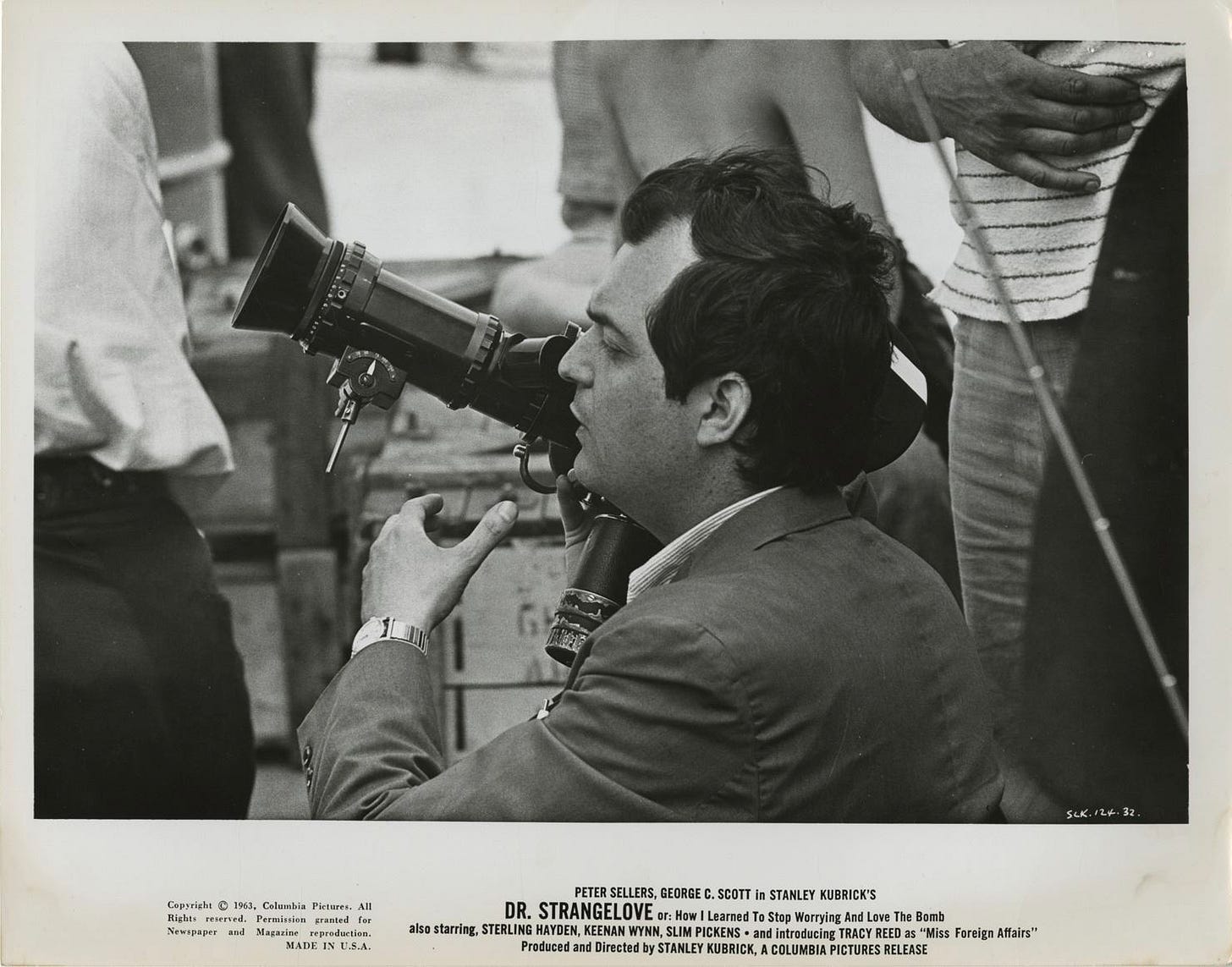

Watch It: "Dr. Strangelove Or: How I Learned to Stop Worrying and Love the Bomb"

dir: Stanley Kubrick (1964)

If you’ve ever wondered how the Coen brothers came up with the idea of having total nitwits deliver verbose, broadly comic dialogue, look no further than Stanley Kubrick’s end-of-the-world satire, Dr. Strangelove or: How I Learned to Stop Worrying and Love the Bomb. I wish I had been cognizant enough (I was hanging out in a crib at the time) to know how people were reacting to this picture when it was released way back in 1964.

At that point, of course, both musicians and filmmakers were tentatively starting to document a shift in our culture toward the forgiving concepts of peace, love, and unity. But Kubrick cruised right past that crap, opting instead to deal audiences a cynical, star-spangled hand of death and destruction.

You have to process information a little differently than everyone else does to view nuclear holocaust as the ultimate orgasm.

Only Kubrick could have reframed a pair of fuel-sharing B-52s as making sweet love to each other to the strains of “Try a Little Tenderness,” an image that plays beneath Dr. Strangelove’s opening credits. Right off the bat, you can tell this movie is a little bit…different.

By the time Kubrick and his co-writers Terry Southern and Peter George are through with you—and Slim Pickens rides a phallic missile to the final Big Bang—you’re worn out from ninety minutes of cackling at technologically enhanced mass murder and the inescapable conclusion that…well…we all might be fucked.

Imagine the Marx Brothers by way of the Angel of Death, with a rewrite by a horny, Mad magazine-loving film professor. And even that doesn’t do it justice.

Kubrick’s doomsday narrative kicks into motion when Gen. Jack D. Ripper (Sterling Hayden), who is shit-crazy, holes up in his office at Burpelson Air Force Base and takes it upon himself to launch a nuclear attack against Russia.

Not even the pleading of one of his key officers, a properly panic-stricken RAF man named Mandrake (Peter Sellers), can convince Ripper to cough up the radio recall code so the bombers can be retrieved before dropping their deadly payloads (eagle-eyed viewers should look for a spray-painted reference to the recall code in the Coen brothers’ bizarro-comic masterpiece Raising Arizona.).

In due course, President Murkin Muffley (Sellers again), Gen. “Buck” Turgidson (George C. Scott), and an assortment of military and political big-shots gather around a massive table in the War Room and try to determine how to either knock the bombers out of the air or, as Turgidson enthusiastically relates, live in a world where there’s “no more than ten to twenty million killed. Tops. Depending on the breaks.”

All the while, a wheelchair-bound “ex-Nazi” genius named Dr. Strangelove (Sellers yet again) waits in the wings, ready to outline the conditions of existence in a brave new, annihilated world.

Throughout this insane debate, Kubrick repeatedly cuts between the War Room and the one bomber that actually breaks into Russian airspace and is still capable of dropping a nuclear bomb. Just so you don’t get too comfortable, the plane’s pilot, Maj. “King” Kong (Pickens), is a gung-ho cowboy whose cretinous devotion to duty might mean that mankind will soon be a thing of the past.

Again, kids—this is a comedy.

Strangelove’s difficult, wacky tone never falters, not for a second. Kubrick’s large cast repeatedly hits it out of the park, and the imminently quotable script all but grooves them the pitch.

Everyone remembers Muffley’s surreally polite telephone conversation with the Russian Premier, in which Sellers tries to assure a man whose country is about to be disintegrated that there’s no need to shout. There’s also Ripper’s theory about the post-war Commie conspiracy’s goal of “sapping our precious bodily fluids.” But line after line after line of dialogue is jaw-dropping in its bite and brilliance. The hits just keep on coming.

Scott—who should have won an Oscar but didn’t—has a couple of extended, dim-bulb militaristic conversations with Sellers that put me on the floor every time I hear them. His performance is an absolute gem of comic timing, one of the finest you’ll ever see.

Scott’s features bounce around like a Superball from one self-satisfied doofus expression to another. Just the way Turgidson chomps his gum while being scolded by the president tells you as much about this character as his outlandishly optimistic speeches about the end of the world.

Turgidson wears machismo as his fool’s armor—which, in case you haven’t noticed, is what extremely powerful men do nowadays. Too bad it can’t remotely protect him from the ultimate horror he’s enthusiastically endorsing.

Bonnie and Clyde is often pegged as the beginning of the modern age in filmmaking, the moment when adventurous free-thinkers took control and started demolishing the cardinal rules of what one could include in a commercial film. A great reimagining, so the accepted wisdom goes, had finally begun.

Well, Bonnie and Clyde is an undeniably revolutionary picture, and many more unconventional movies followed in its wake. Certainly, it cracked open the door for Easy Rider’s rambling hippies and dope. But Warren Beatty and Arthur Penn didn’t get their act together until 1967. Kubrick’s Dr. Strangelove must have occasioned millions of “What the fuck?!” responses a full three years before Penn’s foggy mountain breakdown occurred. Its being produced in England doesn’t change the fact that it was a major critical and commercial success in America.

As unprecedented as it was, people still ate it up. Like Dylan, Kubrick was already fully aware that the times were a-changin’.

I would argue that Dr. Strangelove is Kubrick’s best movie. I’ve grown over time to really admire 2001: A Space Odyssey’s sly, high-toned mind trip, too, but there’s no avoiding the fact that stretches of it could drop the unconvinced into deep Van Winkle sleep. Dr. Strangelove slows down on occasion, but the dialogue continually pops along like a bop drummer working his snare drum.

There’s never been another movie quite like Dr. Strangelove, one that’s so potently bizarre while being grounded in the very real horrors of the modern age, where the lunatics are indisputably running significant wings of the asylum. It never gets old because the world never manages to solve its single biggest problem. And it certainly doesn’t seem like that’s going to happen in the foreseeable future.

Don’t forget to say your prayers.

Seller's interaction with Keenan Wynn is another part of the movie that I love.