In 1978, Marshall Crenshaw, a young guitarist and aspiring songwriter who had been playing in an oldies band in Detroit, realized he needed to quit spinning his wheels and kick his life into a forward gear. After relocating to the theoretically more promising West Coast but failing to find a band that fit his early rock & roll obsessions, he finally auditioned for the part of John Lennon in a national touring company of the faux-Beatles extravaganza known as Beatlemania.

Crenshaw won the role, then had to endure months of people wildly cheering him for pretending to be somebody other than Marshall Crenshaw.

Although, by all accounts, Crenshaw was a credible enough Lennon, he soon realized he needed to find a musical identity of his own or he might be driven insane. So he purchased a four-track tape recorder, and whenever there was a break from the tour, he made demos of his own songs. But they weren’t the sorts of tunes other struggling songwriters were recording on the cusp of the glossy '80s.

“Around '73,” Crenshaw later said, “I just stopped listening to the radio and just became immersed, listening to old 45s from the 50s and early 60s. It seemed to me that there was more immediacy in those records than the stuff that was on the radio at that time."

The tunes Crenshaw wrote rode a wave of starry-eyed lyrics, although the romanticism was more often than not undercut by an Elvis Costello-like strain of barbed sarcasm. He had trouble writing completely committed “love” songs, and the fissure was both amusing and fascinating.

Here’s one of the demos he recorded when he finally got his act together, a catchy Hollies-influenced number called “You’re My Favorite Waste of Time.” Note his already fully developed flair for vaguely melancholic, minor chord-driven melodies. (Crenshaw never recorded an “official” version of the song, but Bette Midler covered it in 1983, and another cover by Owen Paul reached number three on the British charts a few years later.)

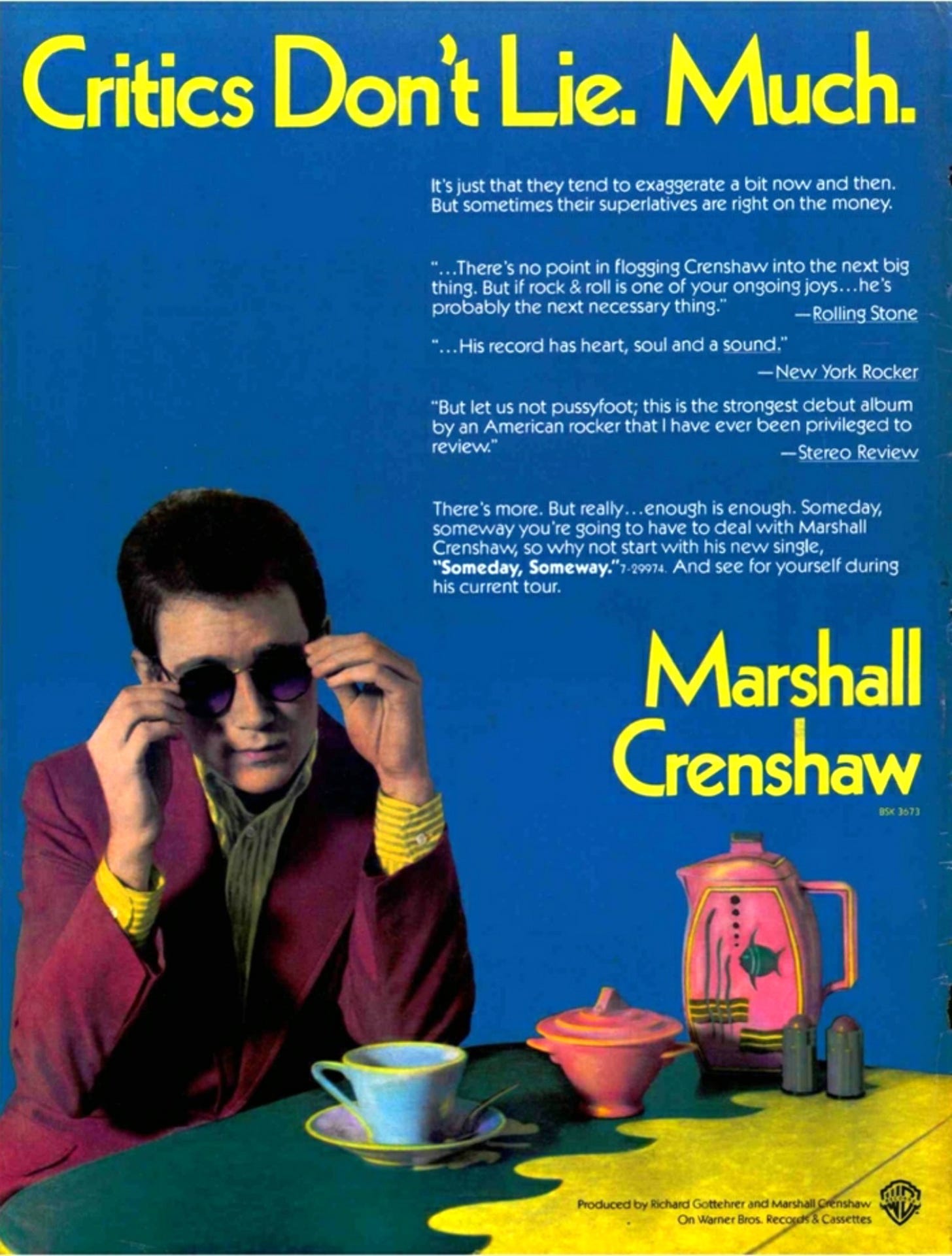

With captivating work like that coming from his bedroom, it’s no wonder record labels were scrambling to sign Crenshaw after hearing his demos. I read about him in Rolling Stone magazine long before I’d heard a single note of his music, and just the description of what he was doing, which included references to Buddy Holly and Phil Spector, got me excited.

Surely, I was the only north Alabama 17-year-old who was listening to the Ronettes while he got dressed for school in 1980.

Soon after signing with Warner Bros. Records in ‘82, Crenshaw entered the Record Plant in New York City with his drummer-brother, Robert, and a superb bass player named Chris Donato, and proceeded to cut one of the coolest, most insanely catchy debut albums since the Beatles initially please-pleased the world.

I’m not exaggerating, either. I flipped out when I first heard it, and so did America’s professional music critics. I can clearly remember listening to it on a set of headphones while lying in bed at night and marveling at the enormously catchy melodies and Crenshaw’s almost magical ability to sound old-fashioned and absolutely modern at the same time.

I felt from my first listen that the record was a genuine classic, and, over the past several decades, my opinion of it hasn’t changed a bit. It sounds as fresh now as it did when I was a teenager.

The story goes that Lou Reed named his final album with the Velvet Underground Loaded because, as he saw it, it was brimming with possible hits. One wouldn’t have faulted Warner Bros. for thinking the same of Crenshaw’s eponymous debut.

Unfortunately for Crenshaw—and for Reed, for that matter—the American public’s musical tastes had skewed mightily toward horseshit while he was still digging the Cool Stuff, so he only managed a very minor chart appearance in the form of a bouncy little number called “Someday, Someway,” which also received a teeny-weeny bit of airplay when it was released by the equally un-purchased rockabilly revivalist, Robert Gordon.

All the other “hits” would be enjoyed only by the relative handful of people who purchased the album, which never climbed higher than number fifty on the Billboard chart.

Everything on Marshall Crenshaw is great— and I mean every single song. The weakest track is easily a cover of an old Arthur Alexander tune called “Soldier of Love,” but even that serves as mortar between Crenshaw’s concepts of rock & roll past and present. You can tell the guy singing and playing the guitar on this album is a rock & roll fan, much in the same way you can detect Bruce Springsteen’s fanaticism on Born to Run.

There’s a joyous sense of creation in the air, as if Crenshaw is openly celebrating his chance to join the lineage of great American pop. And he throws in lots of lyrical hints that rock & roll is a lifeline you can cling to when the real world is simply too much to bear.

This was obviously a man who had bought a few records in his time. And he really listened to them.

Years earlier, Crenshaw’s co-producer on the project, Richard Gottehrer, was a Brill Building songwriter who penned such AM-radio classics as “My Boyfriend’s Back” and “I Want Candy,” so he knew full well where this artist was coming from (Gottehrer would hit the financial jackpot soon after working with Crenshaw by producing the Go-Go’s gazillion-selling debut, Beauty and the Beat.)

Marshall Crenshaw’s bright, bouncy sound is elemental to its appeal. The arrangements are never overly busy, so you can pick individual instruments out of the mix if you want to focus on them. The only thing that could conceivably be viewed as a bauble is the occasional ringing of a glockenspiel. Beyond that, it’s handclaps and high harmony supporting a series of gorgeous, seemingly effortless melodies.

As I already said, there are literally no duds here. It’s tough to choose just a couple of tracks for new listeners to hear, so I’ll give you three. But anything I choose is guaranteed to convey the album’s dazzling effervescence. Let’s start with “She Can’t Dance,” which paints a portrait of the exact sort of swinging-ponytail girl you can imagine young Marshall pining for, and probably not getting, in high school.

There’s nothing especially intricate going on here, at least not on first listen. Pay closer attention, though, and you’ll notice the minimalist perfection of Crenshaw’s guitar chords— he’s laying down a bed of bouncing electricity to support the vocals, and the rest of the trio drives the thing along with boundless energy.

Why kids at the time weren’t assigning number judgments to this on American Bandstand remains quite beyond my understanding. Was it really not as worthy as “Eye of the Tiger?”

Next up is “Cynical Girl,” which is arguably the key song on the album and as close to an anthem as you’ll find in the Marshall Crenshaw oeuvre. An hilarious ode to abhorring the abundant garbage everyone else embraces, it once again sounds like it could have been recorded in 1962 or the day after tomorrow, although the weary lyrics—which I’m including because they’re too great to miss—are something of a giveaway.

Well, I'm goin' out

I’m goin' out lookin' for a cynical girl

Who's got no use for the real world

I'm lookin' for a cynical girl

Well, I hate TV

There's gotta be somebody other than me

Who's ready to write it off immediately

I'm lookin' for a cynical girl

Well, I'll know right away by the look in her eyes

She harbors no illusions and she's worldly-wise

And I'll know when I give her a listen that she

She's what I've been missin'

What I've been missin'

I'll be lost in love

And havin' some fun with my cynical girl

We'll have no use for the real world

I'm lookin' for a cynical girl

Well, I'm goin' out

I'm goin' out lookin' for a cynical girl

Who's got no use for the real world

I'm lookin' for a cynical girl

Yeah, I'll know right away by the look in her eyes

She harbors no illusions and she's worldly-wise

And I'll know when I give her a listen, she

She's what I've been missin'

What I've been missin'

I'll be lost in love

And havin' some fun with my cynical girl

We'll have no use for the real world

I'm lookin' for a cynical girl

In an interview with Magnet magazine many years later, Crenshaw said of the song, “I had the music first. That’s how it always works. As far as the words go, I remember having to go to court to pay a traffic ticket, and the words kinda popped into my head all at once. The meat of the song is where it says, ‘I hate TV,’ which is an oddball thing to say in a rock ‘n’ roll song. Whenever I get an idea like that, that’s almost too stupid to put in a song, I always put it in. The thing about the girl is really window dressing. At that time, I despised about 60 percent of mass culture. Now, it’s up to about 90.”

I can relate, Marshall. I can relate.

And for my final exhibit, I offer you, “Mary Anne,” a classic entry in the long rock & roll tradition of songs named after unapproachable girls. The protagonist, as always on Marshall Crenshaw, is trying to light the love flame, but the winds of disappointment keep blowing it out. And the object of his undeclared affection is in the same boat.

“You take a look around, and all you seem to see/Is bringing you down, as down as you can be/Go on and have a laugh/Go have a laugh on me/Go on and have a laugh at how bad it can be” is hardly the most hopeful lyric, but the soaring harmonies and fragile melody coupled with the obvious yearning in Crenshaw’s voice move the tune into certifiably sad territory.

There’s mere disappointment, and there’s genuine heartbreak, and this song hangs precariously on the cusp of the two. It’s a remarkably concise balancing act, clocking in at a radio-friendly two minutes and fifty-eight seconds, not that any deejays actually played it. But the lack of public acceptance doesn’t make this wistful tune, or the rest of Marshall Crenshaw, any less of a pop masterpiece.

It’s no exaggeration to say Buddy Holly couldn’t have done it any better himself. What a terrific, and terrifically moving, little song.

I intended to stop there, but what the hell. While we’re at it, let’s play the flip side.

One of my favorite Marshall Crenshaw tunes isn’t even on the album— it only appeared on the B-side of “Cynical Girl.” “Somebody Like You” was recorded with a little more muscle than the songs that ended up on the record. The sound is meatier and more modernistic, and the guitar solo punches a bit harder. It's more straight power pop on the order of Nick Lowe or Dwight Twilley than brilliantly retooled classicism.

"Somebody Like You" still appears to be an abandoned experiment, though; there are occasional dropouts and flutters in the left channel that suggest the tape somehow got crinkled or twisted. But the eye-rolling lyrics (“I cannot stand that noise you’re listening to/Why did I ever get involved with you?”) are wholly in keeping with a lot of of the album, and the handclaps and “bop-bop” background vocals are to die for.

The crop of songs that encompass Marshall Crenshaw may not hold the secret to life. But, almost 43 years later, they still hold the secret to the next three minutes while I’m listening to them, and that, for me, defines great pop music. If I’m allowed to bring fifteen albums to that mythical desert island everyone talks about, surely this one’s coming with me, along with the best of the Beatles and several other icons, and I’ll gladly sing along with it until I finally die of dehydration or scorpion stings.

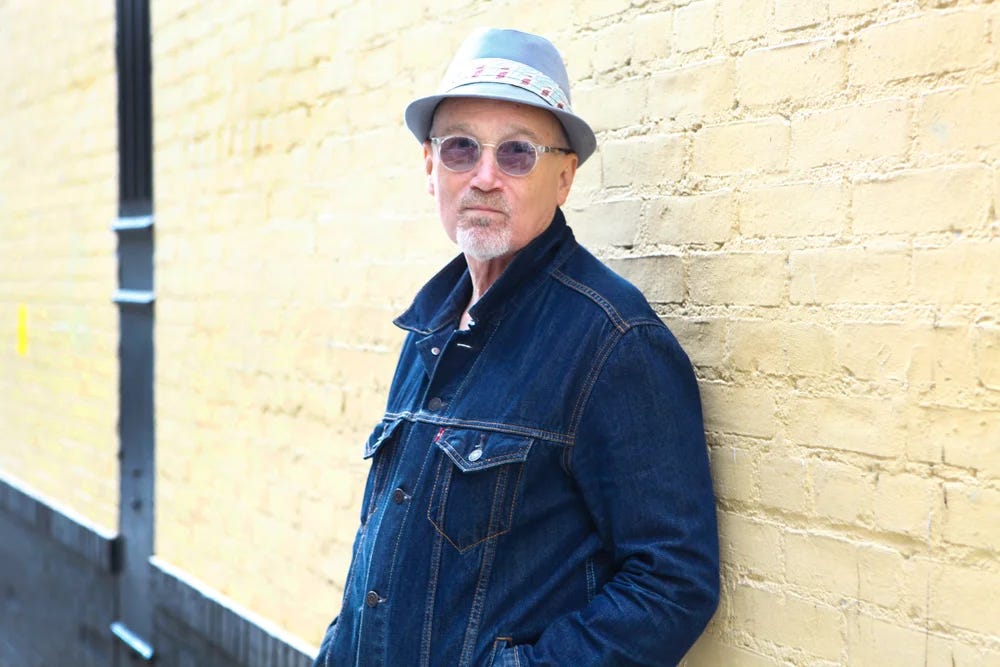

Marshall Crenshaw has released many fine albums since 1982 and is a well-respected songsmith who still tours clubs around the country. But he’s somehow never recaptured the lightning of his debut release, at least not with such energetic, winning consistency.

Back around 1994, my agent at the time needed a date to her old boyfriend’s wedding (they still knew and liked each other), so I agreed to put on a suit and tag along. The ex-beau worked for Columbia Records and, of course, knew many people in the music business. But I was still surprised to see that his buddy, Marshall Crenshaw, led the house band at the reception!

Crenshaw played a lot of obscure ‘60s hits, including a hefty handful by the Sir Douglas Quintet. This seemed dreamlike enough, but I also noticed, sitting among the guests, a sassy-looking woman who smiled broadly while bopping her head to the music.

It was Ronnie Spector, the lead singer of the Ronettes.

I don't believe our lives can really come to one complete circle. It’s more like a series of rough, circular doodles scrawled on a sheet of cosmic notebook paper by an unknowable force. I didn’t speak to either Crenshaw or Spector that evening. I thought it best that we simply share the moment and dig the music, just like we always had, albeit in different locations. There was more than enough connection in that to keep me happy, and other circles remained to be drawn.

For a couple of hours, anyway, the joint was jumping, Crenshaw rocked out, and all seemed right with the world.

What a beautiful balance of intellect and heart. Thank you for Another Great Piece.

Your comment about some of the horse shit music being made in the early 80s when Marshall was also recording: I remember going to Grad Night at Disney World in 1983. All my friends went to see Night Ranger perform. I went to see Marshall Crenshaw to a small crowd. But I danced and sang and it was amazing.

I’ll never forget the way people danced at our friends’ Michael and Amy’s wedding as our band Doc Wiso played Cynical Girl. If ever there were moments in life to capture forever and bottle it, that song and experience was it.

Finally, I also love Whenever You’re on My Mind!

Thanks for writing Paul. Life is better when you write. More please…