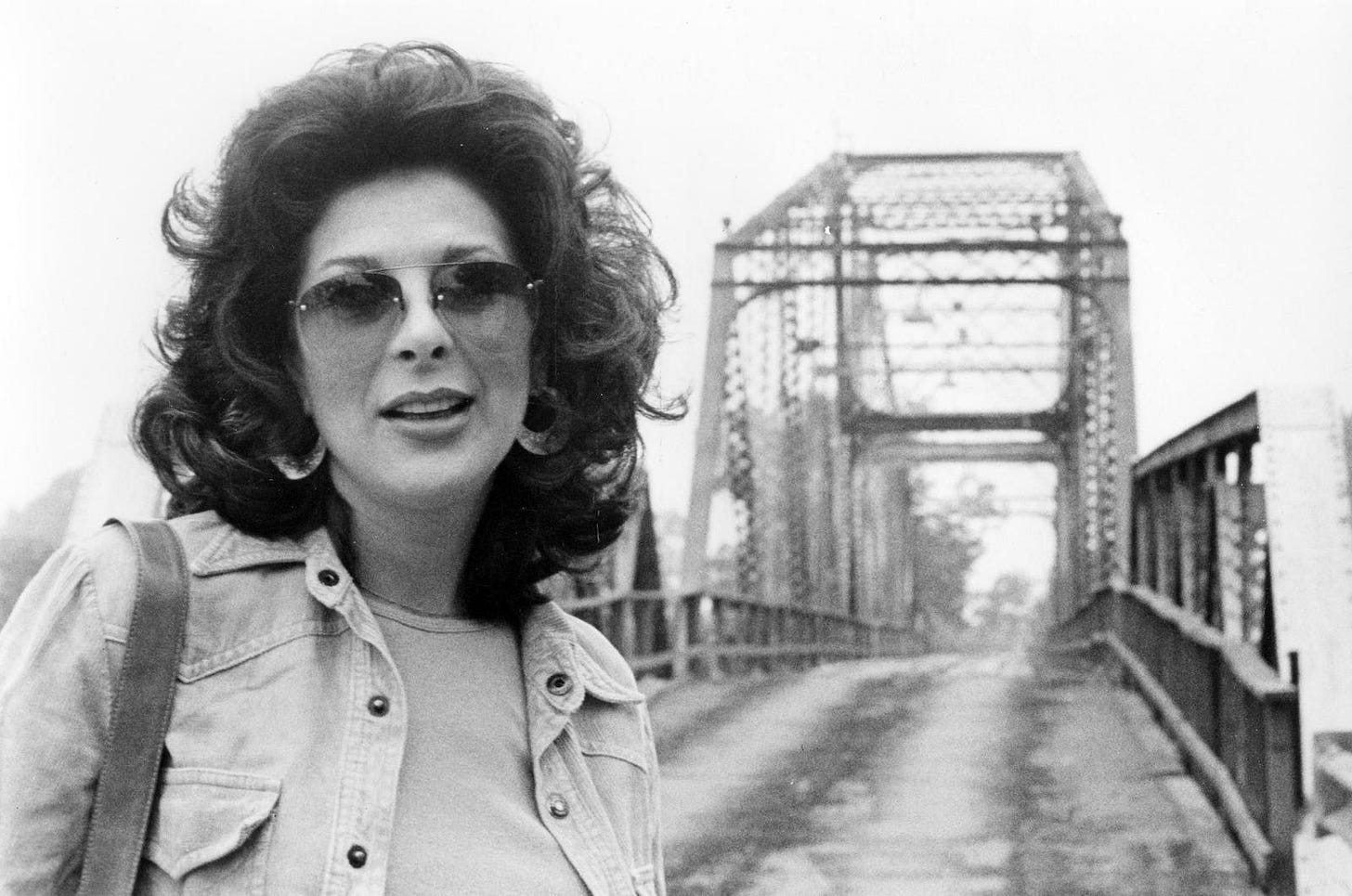

Don’t let the Sixties majorette look fool you—the woman pictured above wrote and recorded one of the more brilliantly unnerving hit songs in pop music history.

Lou Reed paraded junkies and louche S&M queens through New York’s downtown gutters to rattle his listeners. The dread in Bobbie Gentry’s “Ode to Billie Joe” is much more subtle than that, arising as it does from theoretically “Christian,” hard-working country folk who in their own opinion are the irrefutable salt of the earth.

I grew up in a small town in north Alabama, and believe me when I tell you, this sin-free delusion exists. Nowadays, you can even buy yourself a red baseball cap with a bullshit slogan printed on it to advertise your self-anointment.

There’s a certain brand of Southerner who goes to church and says “Jesus” a lot, then behaves any way he or she damn-well pleases, because, as far as they’re concerned, there’s no darkness whatsoever in a small Southern town, unless it’s brought in from somewhere else and foisted upon them like a moral contagion.

Real ugliness is generated in big cities, and those cities pretty much always stand above the Mason-Dixon Line.

In her spot-on portrait of emotional isolationism, Gentry’s characters gossip at length around the family table without saying a goddamned thing...or, at least, nothing about the toll that staring straight ahead, doing your work, and ignoring reality can have on your soul.

The song’s unnamed narrator is a young Mississippi girl who’s come in from the fields with her father and brother to eat the lunch that Mama’s been cooking all morning. Interspersed among requests to pass the biscuits and cut some apple pie, we come to find that Billy Joe MacAllister, an apparent wild child who used to hang out with Brother, has inexplicably jumped from the Tallahatchie Bridge.

Everyone has an opinion about Billy Joe—including Father, who helpfully notes that the deceased “never had a lick of sense” anyway. It’s all perfectly disheartening, but, soon enough, Mama wonders aloud why the narrator hasn’t even touched her food.

The listener begins to wonder, too. There’s a lot going on beneath the surface in “Ode to Billy Joe,” just as there is in any small town where no one dares to say the worst things out loud.

Gentry, in a move worthy of Flannery O’Connor, lets you determine the real story for yourself.

Initially, it’s easy to imagine the girl is simply appalled at the casual way Billie Joe’s death is being discussed. But when Mother notes that the town's preacher thought he saw a girl who looked a lot like the narrator throwing something off the bridge with Billy Joe, a broad range of dark interpretations suddenly come into view.

Surely, the girl must know why this poor kid killed himself. Though the song rolls along on a plaintively plucked acoustic guitar and rising string arrangement, her silence nearly drowns out everything else.

The result is unspeakably troubling if you’re paying attention, a truly remarkable piece of popular songwriting.

Listeners in 1967 grew so concerned with wondering what, exactly, Billie Joe and the girl threw off the bridge—Gentry said she didn’t really know herself, and you’re not supposed to know—they barely noticed the casual ugliness of the rest of the song.

This was not the type of tune that was easy to dance to on “American Bandstand,” but it sold three million copies anyway and was the number one song in the country for three straight weeks. Gentry won a Grammy Award for Best New Artist and Best Female Pop Vocal Performance for her trouble.

Until the age of 13, Bobbie Gentry was raised by her grandparents in rural Mississippi, in a house with no electricity or indoor plumbing. Then she was shipped out to California to be with her newly remarried mother.

Very intelligent as well as strikingly beautiful, Gentry entered UCLA as a philosophy major and did some modeling on the side. When she started singing and playing guitar at some local clubs, she found she really liked it. So she left UCLA and enrolled at the Los Angeles Conservatory of Music, where she majored in composition, counterpoint, and theory!

Gentry had intended to just become a songwriter for other artists, saying that she only sang the vocal on “Ode to Billie Joe” because it was less expensive than getting someone to sing it for her.

Incredibly, the string arrangement was later added to the actual recording she sent to Capitol Records while pitching her songs! They just laid an overdub on the demo, and there you have it—an iconic record!

Gentry’s second album, 1968’s The Delta Sweete, an often dreamlike, unnervingly dark concept piece about life in the Deep South, was far more ambitious than most country albums being recorded at the time. It’s a major record, full of gutsy covers and odd chord progressions in Gentry’s self-penned songs.

Virtually every instrument on the album is played by Gentry herself, including piano, guitar, banjo, bass, and vibes. It’s the work of an ambitious artist who was not taking the easy way out by duplicating the sound and tone of a massive hit single.

And no one could be bothered to listen to it. It only reached number 132 on the Billboard chart.

Gentry, again, was nobody’s fool. She had to have known that she was pushing some buttons with The Delta Sweete and that a lot of country music fans wouldn’t come along for the ride. But she went ahead and did it anyway.

Gentry actually covers Jimmy Reed’s “Big Boss Man” on The Delta Sweete, which, in Reed’s version, is about a man being worked too hard on the job. But Gentry’s sexy, moaning vocal turns the entire thing on its ear. She’ll obviously be doing her work in a bedroom with her big boss man. Later for plowing in the field, if she even gets around to it.

And no other female country artist at the time would have even thought to cover “Parchman Farm,” an old folk blues about a guy who’s murdered his wife and is picking cotton until he drops at the Mississippi State Penitentiary.

This is awful risky revisionism by an artist in a genre that wasn’t necessarily looking for it at the time.

There were independent women in country music in 1968, Loretta Lynn and Tammy Wynette chief among them. But Gentry wasn’t just attacking men for comin’ home drunk all the time. She seemed to be suggesting something was a little bit off in country living in general.

And that’s a big no-no.

The most distinctive track on The Delta Sweete is a haunting examination of loss—of an ambiguous sort—called “Courtyard.” Gentry wrote this one, and her approach to singing it is almost unbearably intimate. You can practically feel her breath in your ear as she whispers into the microphone.

Listen to this. It’s a deeply compelling song, vocal, and arrangement.

As she did with “Ode to Billy Joe,” Gentry leaves the central question of the story unanswered. Is the woman singing about a former lover who’s left her? Has he died tragically? Has he gone off to war? Has he been killed in a war?

The discordant note at the end of the tune strongly suggests something is amiss, if you somehow still aren’t sure, but once again you’ll have to decide for yourself exactly what it is.

Gentry isn’t telling.

Just a handful of months later, Gentry would release Local Gentry, which forebodingly consisted almost solely of other writers’ material. It didn’t make the charts at all.

This was followed by a very successful, wholly conventional album of duets with Glenn Campbell that shot straight to number one. Bobbie Gentry was riding high once again, with Campbell’s considerable help—he was the single most popular country recording artist at that time.

But her solo ambition now seemed to be a thing of the past.

Her next album, Touch ‘em with Love, is a solid piece of Dusty Springfield-style blue-eyed soul featuring only a single original Gentry song and a nice cover of Burt Bacharach and Hal David’s “I’ll Never Fall in Love Again” (several tunes on The Delta Sweete seem overtly influenced by Bacharach’s unpredictable harmonies). A good album, for sure, but Springfield got there first. Gentry was now chasing trends rather than ignoring them.

Once again, the record tanked.

Touch ‘em with Love was followed by a series of unexceptional albums that played up Gentry’s underappreciated voice more than any thematic underpinnings. They were smooth stuff, unlikely to offend anybody, and were far less interesting than her initial output as a result.

Even though Gentry claimed its commercial failure didn’t bother her, she seemed almost chastened by the shrugging response to The Delta Sweete, as if she’d been well and good put in her place for biting off too big a piece too early in the game and decided to pull back to something less challenging from there on out.

It’s hard to say if the tunes stopped coming for her or if she simply didn’t care all that much anymore, but she didn’t keep it up for very long. Her final live performance came in a Mother’s Day TV special on NBC in 1982.

Then she just stopped. She officially retired from show business altogether at the age of 40.

The last time anybody checked, Bobbie Gentry was living comfortably on her songwriting royalties in Los Angeles. For many years, she was actually a partial owner of the Phoenix Suns! After three marriages that lasted less than two years each, the last one ending in 1980, she has remained unmarried.

She hasn’t made an official public appearance or sat down for an interview in over forty years and is now 82 years old. This is a woman who knows a thing or two about dramatically withholding information, that’s for sure.

This was great. Thank you for revealing more insight on Gentry’s career. I have a favorite playlist of The Delta Sweete with each song followed by its cover version by Mercury Rev and guests. They show great love and respect for what she accomplished, in my opinion.

I like to think your appreciation would bring her out for an interview.