I am not exactly what you would call an animation buff. I can appreciate the work that went into an old, hand-animated cartoon without getting particularly caught up in it. Even when I was a kid, there was something off-putting about Mickey Mouse. I couldn’t have articulated David Bowie’s assertion that Mickey had “grown up a cow,” but I sure could sense it.

There’s always been a whiff of U.S. Steel about Walt Disney, in my opinion. He may have been a genius, but you can tell he’s looking for the masses to genuflect. He constantly seems to be trying to win an Oscar. It’s off-putting.

I don’t want to be forced into submission by an elaborate rendering of a commercially-tooled fairy tale, and it always creeped me out that a prince would kiss a good-looking corpse. I like cartoons where people pointlessly slap and punch and kick each other, with maybe a few choice one-liners thrown in for good measure.

Basically, I prefer animated characters who are coarse and kind of stupid.

Which brings us to the Popeye the Sailor series that Fleischer Studios, under the guidance of the brilliant Fleischer brothers, Max and Dave, created in the 1930s.

Popeye started out as a widely-read E.C. Segar newspaper comic strip in 1929. In 1932, King Features Syndicate, which distributed the strip, enlisted the Fleischer brothers (Max was the producer and Dave the director) to turn Popeye’s adventures into a series of animated shorts for Paramount Pictures.

The Fleischers knew what they were doing. They had been in the film animation game from its inception, having already created Koko the Clown, one of the first popular silent cartoon characters. And they were responsible for the Betty Boop series, too, a veritable cultural phenomenon that only waned when pearl-clutching Hays Code censors objected to the character’s sexiness and forced the Fleischers to tone her down.

The brothers’ first Popeye cartoon was released in 1933. They quickly had another hit on their hands, this one with real staying power.

No one was going to accuse Olive Oyl of being too sexy.

Don’t expect to be awed by the glory of human existence while watching one of these things. And don’t worry about losing track of the plot or missing out on the subtext. There isn’t one, and there isn’t any.

More often than not, this is the basic libretto:

Popeye, continually muttering to himself like a pipe-smoking bag lady, is in love with Olive Oyl. Bluto, ornery for no apparent reason, shows up and lusts after Olive. Sometimes Wimpy is seen ordering a hamburger. Soon enough, Bluto mistreats Olive, often to a shockingly physical degree, and Popeye finally draws the line.

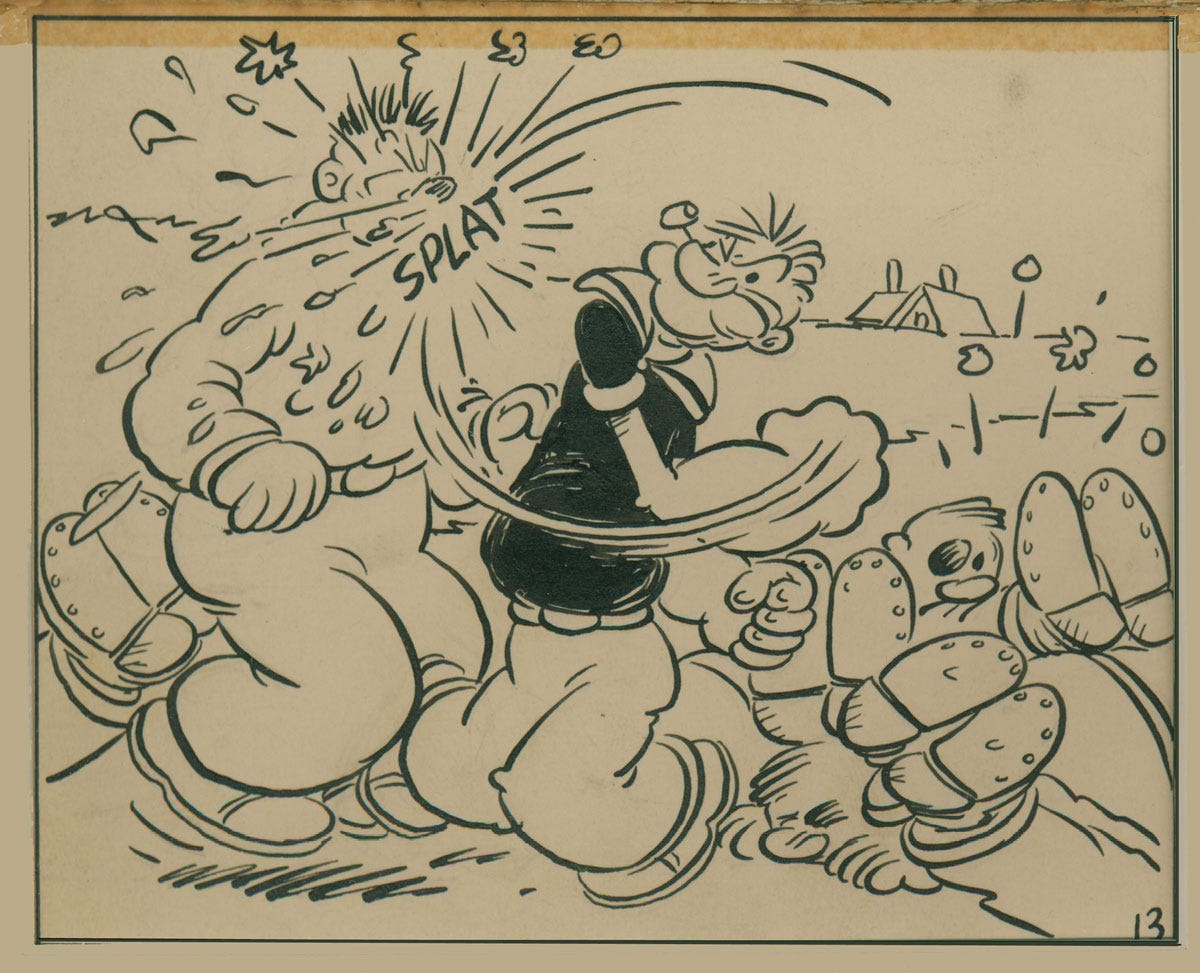

Popeye and Bluto then preposterously punch, gouge, stretch, kick, twist, elbow, bite, and strangle each other for possession of Olive and her stick-like charms, although Bluto’s obvious weight advantage appears to be too much for Popeye.

Then, just when all seems lost…

Cue the music!

Our hero finally manages to remember that eating the giant can of spinach he’s somehow been carrying on his person the entire time will give him incredible strength, which instantly enables him to stomp the holy crap out of Bluto.

Moral brought to you by the Spinach Association of America.

Popeye, rather oddly, but admittedly not much odder than everything else that’s going on, had a remarkable gift for punching animals and converting them into furniture, carpeting, leather goods, lamps, and a wide variety of perishables.

He did this a lot.

In this shot, for instance, he’s just belted a charging bull, which caused the bull to explode and reconfigure its being into a fully functioning butcher shop. (Note that some of the meat is kosher. The Fleischers were Jewish.

And here’s a jungle full of wild beasts that Popeye just turned into a complete winter lineup with nothing more than repeated blows from his iron dukes, driven as they are by his alarmingly thick, anchor-tatted forearms.

Check ‘em out! Excluding the factory reject that still has its head attached, tell me you wouldn’t wear those coats, ladies.

I thought so.

Had Popeye only stopped to think about it for a couple of seconds—not exactly his strong suit—he could have turned this unique skill into his own business, sort of a proto-IKEA with clothing and meat departments, born of nothing but kicking ass and taking names. Seed money not required.

The Fleischers were Brooklyn boys, the sons of Polish immigrants (Max was actually born in Poland), and, much to their credit, they were not cutesy like Disney. Popeye existed within a somewhat wacky version of the industrialized 1930s, full of rickety buildings, brick roads, steam-belching machinery, and rocking boats.

The settings are almost as enjoyable as the action. In fact, Max created, in conjunction with another animator named John Burks, a way to animate incredibly realistic backgrounds for Popeye to inhabit. They called it the Stereoscopic Process.

Small, detailed models of the necessary scenery—houses, buildings, trees, telephone poles, etc.—would be placed on a circular table, more or less a large Lazy Susan. This set would then be photographed through animation cels of the moving characters while the table was rotated past them, creating the illusion of Popeye and the gang moving through a real, non-animated environment.

Here’s an example image.

This remains a startling effect. It’s quite unlike anything other animators were doing at the time. I can remember watching these cartoons as a kid and getting a big kick out of it.

Considering the amount of goofy charm on display, it’s surprising how much aggravation and infighting was involved in creating Popeye the Sailor. It eventually brought the whole thing tumbling down.

The first big headache came from the guy who initially supplied Popeye’s voice, an ex-vaudeville performer named Billy Costello. Costello invented the gruff mumbling we all immediately recognize today as being that of Popeye, but after working on the first twenty-four episodes of the series, he was fired by the Fleischers for demanding more money, insisting on days off in the middle of recording sessions, and just being an overall goddamn prima donna.

That didn’t stop Billy, though. He then launched a European stage tour during which he utilized his Popeye voice. He even recorded a series of Popeye-style novelty records that were only released overseas to avoid lawsuits from the Fleischers and Paramount Pictures!

Here’s one from 1937 called “The Merry-Go-Round Broke Down.” It’s bizarrely catchy, in its limited way, and even features a bit of unexpected scat singing from Popeye. (Note that the melody is immediately recognizable as the Looney Tunes theme music!) I’m not sure if Warner Bros. stole the idea from Costello or the other way around, but my money is on Costello being the shifty one.

It ain’t “The Purple People Eater,” but what is?

Sadly, the end of the Fleischers’ version of Popeye—other animators would carry on with less-inventive work for many years afterward—came about due to a bad contract with Paramount and the brothers themselves having a falling out.

Paramount started demanding more and more Popeye cartoons, and the workload was too much for Dave Fleischer and his animators, many of whom quit and high-tailed it over to Disney. Max eventually had it up to his neck and wanted to dump Popeye in favor of making more ambitious films, but Dave saw no need to give up on Popeye while it was still so successful.

This led to arguments and Dave wresting control of Popeye from Max. The brothers finally told Paramount they wanted to move on from Popeye, but it was not smooth sailing... no pun intended. Although they still created a truly spectacular art deco Superman series (I’ll almost certainly cover it one day here at “The Cool Stuff'“), their two forgettable feature films paled in comparison to Disney’s, due to underfunding from Paramount.

Dave finally moved out to California to produce a handful of cartoons and do technical work at Universal. Max, for his part, basically gave up altogether, focusing instead on working on inventions—along with the stereoscopic process, he had also invented rotoscoping—and teaching.

They never made up with one another.

Let’s not end with that bummer, though.

Did you know that the character Popeye was inspired by an actual human being? His name was Frank “Rocky” Fiegel. This is the only known photo of Fiegel (there are others widely circulating on the Internet, but they aren’t really him.)

Fiegler was a drunken, hard-as-nails bartender and brawler in Chester, IL—hometown of E.C. Segar, the creator, as I’ve already mentioned, of the original Popeye comic strip.

Fiegler used to get plastered and fall asleep in a chair in front of the bar where he worked, enjoying the sun. Segar and his childhood friends would sneak up close to Fiegler and scream, just to make him jump out of the chair, then mutter to himself and sit back down again. It seems unlikely that he used to squeeze cans of spinach into his mouth and punch wild animals into luggage sets. But Segar never specified, so let’s just assume that he did.

Fiegler died in 1947 at the age of 79, probably having been too gassed for most of his life to get around to suing Segar. There is, however, a picture of Popeye engraved on his tombstone, which is so cool it would likely make up for those little kids screaming at him all the time, were he only alive and able to see it.

That is so cool! I’ve watched a few Betty Boop episodes, not Popeye yet or Superman. So interesting to learn about the stereoscopic process too. The creativity of these early artists always blows me away.

The Fleischers were Jewish!?