A couple of much younger guys I work with are forever arguing over which NBA player is the legitimate GOAT—an overused acronym for “greatest of all time.” Not surprisingly, given the attitudes of modern Americans, their knowledge of NBA history begins with Michael Jordan’s rookie season in 1984. If a player didn’t get to take four steps before shooting and scream and pound on his chest like Tarzan after hitting the shot, he doesn’t count.

This means they’ve landed on Jordan, LeBron James, and Kobe Bryant as the only real candidates for the NBA’s single greatest player. Anyone who played before those three showed up is a black & white movie on TCM and not worth pondering.

I’m getting sick to death of listening to their endless citations of these three names. I told them the other day that they should switch to arguing about the existence of God, which is just as unanswerable, and almost certainly more important than whether Jordan was more clutch than LeBron is in playoff games against totally different teams in totally different seasons.

I am no fan of GOAT arguments. I think they’re ridiculous, and I hate that grotesque acronym. But I’ll guarantee you there are more than three players whose names should be included if you’re looking to have a real discussion about the greatest basketball players who ever lived, even if you’ll never reach a definitive answer as to which one was the best.

Come with me, then, as we journey to the early 1960s, a miraculous time when professional basketball players could take only two steps while holding the ball and driving to the basket, simply because that’s what it says in the rulebook! Imagine that! And if they nailed one from half-court, let alone from a few steps above the key, it counted for exactly two points, just like a regular ol’ layup.

Back in those days, nobody thought to trademark a silhouette of themselves dunking the ball behind their head so it could be plastered on overpriced merchandise. But one athlete dominated the sport to a degree that was very nearly equal to Babe Ruth’s unchallenged sovereignty over major league baseball in the 1920s.

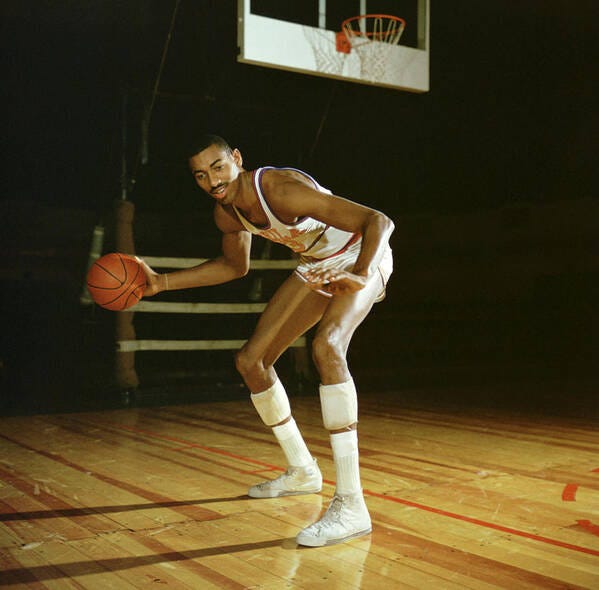

I’m talking about, of course, 7-foot 1-inch Wilton Norman “Wilt” Chamberlain, aka “Wilt the Stilt.” That’s Wilt in 1959, the year he played for, of all teams, the Harlem Globetrotters.

At the time, the NBA wouldn’t accept a player straight out of college if he didn’t finish his last year of classes. So Chamberlain, who was sick of being triple-teamed and watching his opponents freeze the ball for minutes at a time in order to avoid confronting him during an actual play for the basket, left the University of Kansas to bide time with the Trotters. This allowed NBA players to breathe easily for another season.

But they knew he’d be coming in 1960, and, when he did, the game was literally changed forever.

Drafted by his hometown Philadelphia Warriors, Chamberlain scored 43 points and pulled down 28 rebounds in his first-ever professional contest...not that it was much of a contest.

He would average 37.6 points and 27 rebounds per game during that 1960-61 season, numbers that were (and remain) so utterly sick, new rules were eventually instituted to try to keep the guy at least a little bit in check.

First, the lane was widened so he couldn’t hang out waiting for an easy dunk, and the concept of offensive goaltending was also introduced. My personal favorite, however, is that the league decreed Chamberlain could no longer leap from the line during foul shots and deposit the ball when he was just a couple feet away from the basket!

I’ve never heard of another professional sports league that substantially altered its rules because one player was so overwhelmingly talented others couldn’t compete with him.

This wasn’t simply a matter of Chamberlain being bigger than everyone else, either, although even when little Paulie was rooting for him in the early 1970s, he was still a more impressive physical specimen than virtually anyone else on the court. Chamberlain was graceful. He could move; there was nothing lumbering about the way he carried himself.

One of Chamberlain's least-heralded but still astonishing exploits is that he never fouled out of a game. Never!

He wasn’t falling on top of Lilliputians while he stumbled around the court. He was a basketball player, an absolutely brilliant basketball player who happened to be as big as a fucking tree, and he played against other men who earned the right to compete in the NBA.

They didn’t fill rosters with whoever was passing by the arena in those days, regardless of what people now want to think. These were the best basketball players in the country at the time. Sure, Chamberlain’s height gave him an advantage, but no one ever argues that Jordan was really good, but that was just because he could jump higher than his opponents.

Chamberlain was competing against fellow members of the human race who were very good at playing basketball, and he was stomping the living shit out of them.

Yes, he was tall. And he was also that much better than everybody else. There’s a lot more to playing the game at the professional level than simply having a height advantage.

It’s a sports truism that statistics don’t tell the whole story, but there’s no denying they can tell a considerable chunk of it. Chamberlain’s stats read like a tall tale told by somebody’s grandpa—he was Paul Bunyan in satin shorts, minus the big blue ox.

His numbers are so impressive they appear to be misprints when you compare them to those of the stars who followed. Check these out, all of which remain records, and by a considerable distance:

Chamberlain averaged 22.9 rebounds per game for his career and 27.2 for the 1960-61 season. Just as a random comparison, Shaquille O’Neal—maybe you’ve heard of him—averaged 10.9 for his career. His highest average for a season was 13.9.

Chamberlain once pulled down 55 boards in a single game, and he grabbed 46 another time. He totaled 1,000 or more rebounds in a season 13 different times!

Wilt averaged 50.4 points per game (!!!) during his 1961-62 season with Philadelphia, which is almost supernatural. Jordan’s best was 37.1. Nowadays, 50-point games are rare enough that they’re the talk of the league for a few days when they occur, and today’s totals include three-pointers. There was no three-point line in the NBA until the 1979-80 season.

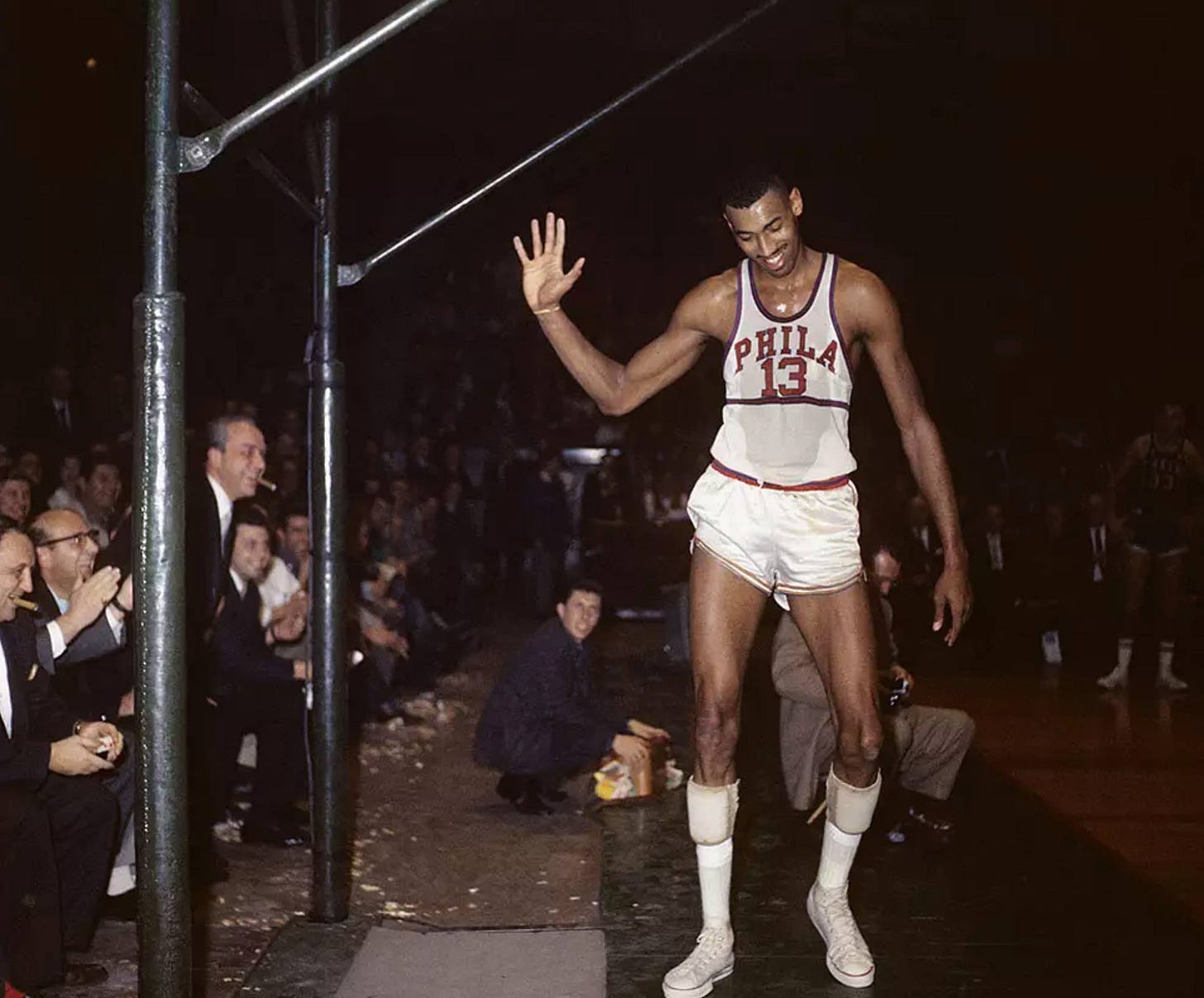

And, of course, there’s Wilt’s signature achievement, a feat so staggering it truly doesn’t sound possible. On May 2, 1962, during a game against the Knicks in Hershey, PA, Chamberlain scored 100 points. By himself. It’s like something you’d pretend to do in your bedroom with a Nerf basketball rather than actually pulling it off in the NBA.

Philly’s home crowd had already seen Chamberlain score more than 60 on multiple occasions, so no one, including Chamberlain, was expecting 100 when he hit the locker room at halftime with 41 under his belt. But even the Knicks’ quadruple-team defense couldn’t stop him in the second half, and he hit the century mark on an alley-oop dunk with under a minute to go. He also nailed 28 of his 32 free throws, which would normally suffice as a good game all by itself.

To put this in further jaw-dropping perspective, Kobe scored 81 in a game back in 2006. Even with the benefit of three-point shots, it was quite an achievement, and he deserved all the recognition he got at the time. But he was still 20 points away from passing Chamberlain’s single-game record.

To paraphrase Edward G. Robinson in The Ten Commandments, “Who’s your Messiah now?!”

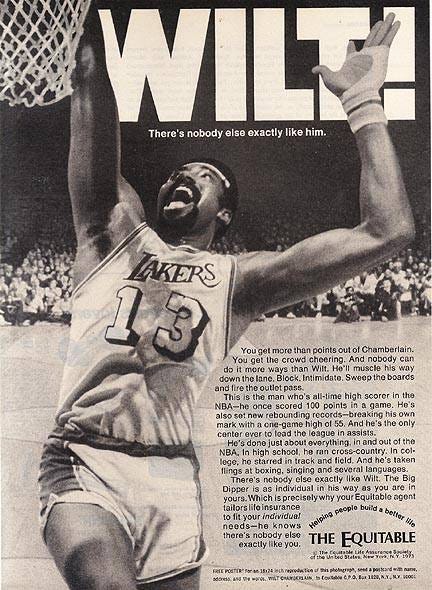

By the time I became aware that Chamberlain was several steps removed from the rest of humanity when it came to all things basketball—I had the above poster, a life insurance company promotional giveaway, hanging on my bedroom wall when I was 8 years old—he was playing for L.A. and had actually “filled out" to over 300 pounds of solid muscle.

But Chamberlain was forever haunted by the fact that his arch rival, Bill Russell, guided the Boston Celtics to an astounding 11 NBA championships while Wilt had managed only one with the Sixers.

Russell and Chamberlain were generational talents plying their trade in the same generation. However, Russell benefited from being a member of one of the most brilliantly operated organizations in sports history. He was surrounded by future Hall of Famers, and, every bit as importantly, Boston had lesser players who knew how to make the stars shine that much brighter.

Chamberlain, more often than not, was pretty much left to do it all by his lonesome; he was Dylan, and Russell was a member of the Beatles. For that matter, Red Auerbach was George Martin.

It was only in 1972, when the Lakers set then-records for consecutive wins and most wins in a season, then took the NBA title, that Chamberlain was fully embraced by the game he altered.

The word “superstar” gets bandied about far too often in modern sports, but if anyone who’s played basketball in the past 50 years deserves the title, it’s Wilt Chamberlain. There was a pedestal permanently affixed to his sneakers.

And yes—Jordan was Jordan, and LeBron is LeBron. Get back to me when you determine which one was the best, then, just for the hell of it, I’ll argue it was Kobe.

Bill Simmons can drive me crazy, but I urge you to read “The Book of Basketball.” He genuinely knows the sport, and though he ranks Russell ahead of Wilt (love your Beatles comparison), he gives Wilt his due. (Though he’s now 9th, acccording to an update.)

Remember when goat meant loser, or scapegoat? Bill Buckner, that sort of thing.