Up until the summer of 1993, I was a committed rock & roller. I mean I lived by those Chuck Berry chords, as filtered through The Beatles, The Stones, Bob Dylan, Bruce Springsteen, and a slew of others who kicked my mind into high gear back when I was 15 years old. I listened to and read about the music on a nearly daily basis.

Along with watching and dissecting challenging, character-driven movies, rock music was the beginning, middle, and end of how I absorbed life. Rock & roll and movies made me look both inward for answers and outward to find new and interesting experiences. This was how I began to generate my personal worldview.

But I eventually knew so much about rock I could even name the best albums by major artists who didn’t necessarily ring my bell (Eric Clapton—461 Ocean Boulevard and Slowhand, unless you count Layla and Other Love Songs, which is technically by Derek and the Dominos).

I finally realized that there’s tons of great non-rock music out there, and I needed to start exploring it.

I worked at a huge HMV Records location at 86th and Lexington here in Manhattan at the time. So I asked to be transferred to the jazz department. Then I bought a couple of jazz encyclopedias and books full of record reviews and systematically set about becoming at least moderately fluent in the music's history.

I had long assumed that jazz was an esoteric form of music that I wouldn’t be able to get into even if I tried, that it mostly sounded like unbound noise-making to a non-musician like myself.

It turned out I was wrong about that. There are many styles of jazz, and even within its standard array of approaches, it’s up to the musicians to play off of one another and create their own particular vibe within that setting. That’s why you’re listening, to hear what they do with it. This is an organic, dramatic process, and more often than not, it’s extremely inviting—you catch the wave and ride it.

Is some jazz too chaotic for my tastes? Absolutely. But there’s no way to put a defining stamp over the entire genre. It’s simply impossible to do that. And I can sometimes find emotional depth or breathtaking musicianship in what initially seems chaotic to me.

Little did I know that I would soon become a straight-up jazz-head as well as a rock & roller, with the fifth edition of The Penguin Guide to Jazz becoming something of a Bible to me. Every bit of this was a new testament; the sum total of my knowledge of jazz up to that point had been the names Louis Armstrong, Miles Davis, Charlie Parker, Dizzy Gillespie, and John Coltrane.

I knew those guys were supposed to be geniuses, but that’s all I really had for you.

This was before the Internet. You didn’t just hop on your computer or phone and click an icon to hear just about any piece of music that’s ever been released. You had to find it and buy it.

So I read up on jazz’s legendary artists, determined which of their recordings are considered their most significant, then got to my job early each morning before my shift started, where I ripped open any CD I wanted to hear and played it at top volume before the manager showed up. Then I snuck in back, resealed the disc with the shrink wrapper, marked it down a couple bucks, and dropped it in the “used CDs” bin.

Shhhhhhhh. Don’t tell anybody. There must have been jazz aficionados going nuts as they dug through the bins and found, for instance, five of the greatest albums by Charles Mingus—remastered, no less—and marked down to nine bucks apiece.

I wasn’t sure at first if jazz would get its hooks into me. But shortly after I began my self-tutoring, it did. I bought my own copies of obviously landmark albums by Miles, Monk, and Coltrane and entered into a new obsession.

I remember the exact tune that permanently flipped the jazz switch for me, too.

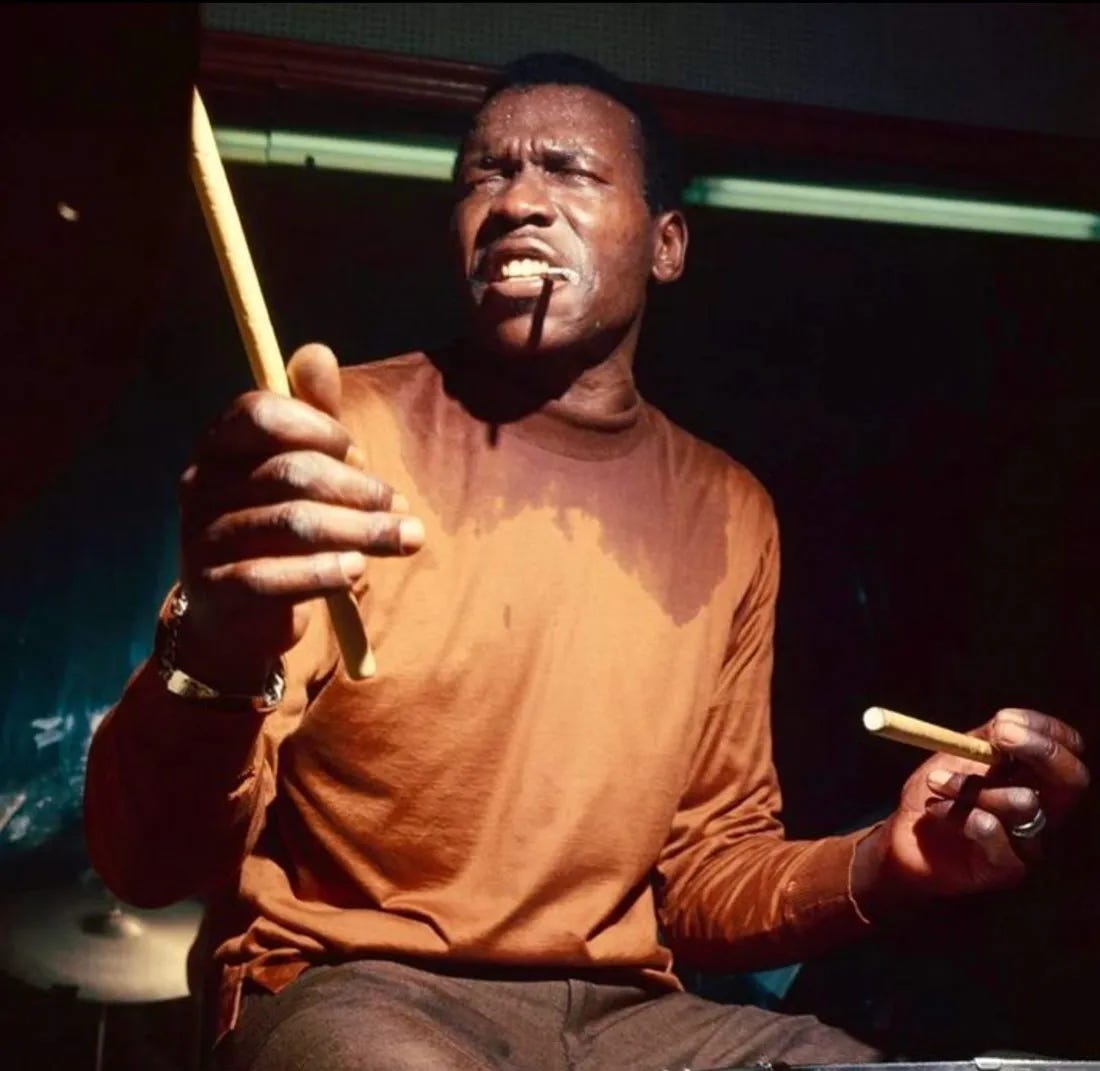

I was in bed with the headphones on late one night when I heard what I thought was two men playing drums simultaneously, a swirling, popping, vaguely surreal swing that rose and fell like the tide crashing on rocks, then spun out into little whirlpools of sound. Then it would rise and crash down again.

This continuous wave of polyrhythm wasn’t played by two men, though. It was one guy named Elvin Jones, and he was the most technically astonishing drummer I had ever heard.

He still is, by a mile.

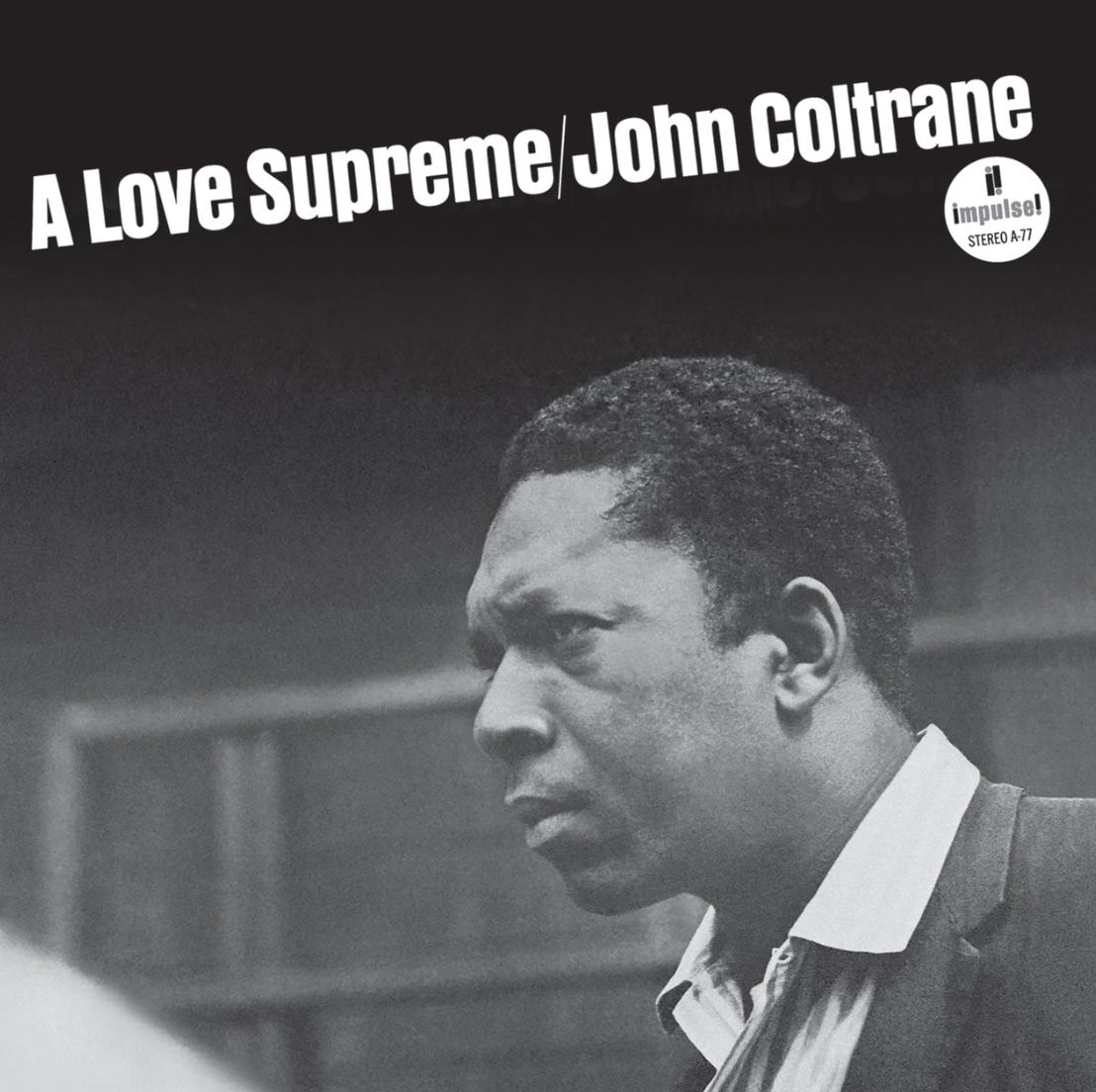

“Acknowledgement" is the first track on John Coltrane’s highly acclaimed 1964 masterpiece, A Love Supreme.

A lot has been made of the spiritual aspects of this particular album. Certainly, there’s a searching intensity to the music, a sense that Coltrane and his band members are tearing at the fabric of every preceding development in jazz, from Armstrong all the way through Charlie Parker and his fleet-fingered progeny.

LSD wouldn’t be hitting rock & roll in a big way for several more years, but Coltrane—who had already overcome the requisite heroin addiction—was using his tenor sax to sonically push into the unknown, drugs not required. He was on a personal quest and was very open about it.

There are many jazz albums that I listen to more often than A Love Supreme. But none of them generate such a clear sense of adventure, a feeling that the men playing the music have entered a realm lying beyond the reach of those who haven’t learned how to pick up an instrument and turn a melody, and even a rhythmic pattern, inside out.

Take that hit of acid, in other words, and maybe you do sense a shaman when you listen to this.

Coltrane, of course, is Coltrane. Complaining about his expansiveness is akin to suggesting the Grand Canyon is just a big ditch. Personally, I’ve always felt he delivered his most listenable work under the watchful eye of Miles Davis, whose sense of structure—at the time Coltrane played with him, anyway—always kept his band members from swimming too far from shore when it was their turn to cut loose.

Miles, the famous story goes, once asked Coltrane why his solos were always so long, and the saxophonist said, “Because I can’t figure out how to stop.” Miles responded, “Try taking the horn out of your mouth.”

A Love Supreme, though, is a soaring experimental work that somehow still connects with unschooled listeners. Millions of people who usually won’t get near such committed rule-breakers as Cecil Taylor or Ornette Coleman, myself included, still manage to find the unearthly hooks in “A Love Supreme.”

Coltrane bleats and growls and sways and roars, but in the service of a greater good than just seeing how many math problems he can solve by reconfiguring the changes. This is challenging music, but a focused listener can still get lost in it. The album, from beginning to end, sounds nurtured by flashing lightning and rolling thunder.

It shouldn’t hold together as a statement, but it does, and the statement feels profound.

That cohesion is where Jones comes in. The John Coltrane Quartet is, without a doubt, one of the three or four most significant bands in jazz history. McCoy Tyner, along with the far more ethereal Bill Evans, is the most influential piano player to hit his peak in the 1960s. Tyner was a genius of pianistic high drama. And bassist Jimmy Garrison could find the rock bottom in wildly obscure settings, the aural equivalent of pouring a building foundation in a mudslide.

As a group, these guys were incredible, almost telepathic in their ability to raise a cathedral of sound on that foundation. But it simply wouldn’t have worked if Jones hadn’t been there to keep it all swinging so miraculously. He was a metronome from a different dimension, a player who could find the unheard groove in a team of police sirens, if that’s what was needed.

I suppose the closest thing rock has ever had to Elvin Jones is Mitch Mitchell, the dynamic, muscular drummer of the Jimi Hendrix Experience. But Mitchell, and I have nothing against him at all, is practically a frat house bongo player when compared to Jones.

On “Acknowledgement,” Jones starts off with a prayerful clash of a gong, then washes into the tune on his cymbals. Then comes a series of rim shots and bass drumbeats that establish a compelling, dark-hued drama. Once Coltrane enters, Jones accelerates the beat while maintaining the continually ringing cymbal.

But that’s just part of it.

Max Roach, one of the founding fathers of bop drumming, was known for “dropping bombs” while he played— that is, periodically stomping down on the pedal to keep the tune moored in the most basic of drumbeats while he tirelessly worked the cymbal (“tick-tick-tick-tick-BOOM-tick-tick-tick-tick-tick-BOOM”). Here, Jones works the bass pedal like crazy, as if he’s caressing Coltrane with a loving barrage of artillery (“tick-tick-BALOOM-BALOOM-tick-tick-BALOOM-BOOM-BOOM-BOOM-tick-tick-BOOM-BOOM-BOOM-BOOM”). I defy anyone to listen to this for the first time and not be astonished by what they hear.

Wynton Marsalis has said it’s amazing that Jones could even imagine playing like this, let alone actually sitting down and doing it flawlessly. Once, when an interviewer asked Jones how he and the other members of the quartet could endlessly expand on Coltrane’s far-reaching concepts with such focused power, he answered, “You’ve got to want to die for the motherfucker.”

That’s what A Love Supreme sounds like. It’s one of the most intense recordings in all of jazz. On that night in 1993, it convinced me to let jazz into my heart and soul, and I’ll never get tired of exploring this indefinable form of music. Every time I hear a great performance, I go on a new adventure.

If you’ve always held jazz at arm’s length, I really wish you’d delve into it a little more deeply. You may be very surprised at what you find.

Brilliant Paul.

Always love your writing, this had so much palpable passion and your typical intelligence, insight.

I go back a long way to recall my soul satisfying immersion into jazz at about age 19 - although my mother turned me on to some of her great 78(RPM)records before that.

I delved into all styles of jazz and it stretched my curiosity and wonder, my imagination, my awe of where music could take me. A journey of surprise and vast delight.

I don't listen as much these days. Not sure why… don't put on as much music of any kind, although I'm constantly singing.

But, I hit the link to Love Supreme, not heard for decades, and the myriad layers of creative genius shot into me like the best drug imaginable. All enhanced by your vivid, reverent, descriptive, observation of the piece. You guided me.

Thank you!

Elvin Jones. My god… incomparable.

As a young man living near NYC, in New Rochelle, I got to see many greats in the jazz clubs of the 70s. Roland Kirk, Sonny Rollins, Max Roach. Modern Jazz Quartet to name a few. (Milt Jackson once autographed my Converses - I didn't have any paper)

At "Glen Island" in New Rochelle, I saw a quintet including Elvin Jones, McCoy Tyner, Roland Kirk at a daytime show in a large venue that only drew about 30 people. My friends and felt like we at a private party with these legends.

Elvin was a force that day.

Paul, you always come with the best of the cool stuff and this post is a highlight. What a gift.

I'll be listening to more jazz straight ahead.

I love this. You write some beautiful music.